The Scary List Method

Leaders of mid-sized companies often ask me, “How can we get more clients?” It’s a good question, and it usually leads to a conversation about making two lists.

The first list is the one you’d expect. It’s a list of all the things you think you should be doing: go to more conferences, ask for referrals, up your social media game. It’s the sensible, comfortable list.

Then there’s the second list. This one’s very different. It’s a list of things that scare you shitless.

Now, I’m not telling you to do any of these things. What’s terrifying and risky for one leader is a walk in the park for another leader. The specifics aren’t the point. But to give you a feel for it, the scary list might include things like:

*Firing your biggest, most time-consuming client.

*Doubling your prices overnight.

*Publishing your “secret sauce” for the world to see.

*Inviting your top three competitors to a private dinner to talk about the industry.

Again, these aren’t recommendations. You’re on your own to figure out what’s on your list. It’s not the specifics I want to hammer home. It’s the vibe. It’s the act of going towards what scares you. That’s the important part.

Why? Because the comfortable list, by its very nature, points you toward more of the same. It’s about optimizing the known. The scary list, on the other hand, points you towards growth and the unknown and the things that will force you and your organization to evolve.

Of course you needn’t do everything on your scary list. But you can’t ignore it. Your job is to always be seeding some of those ideas into your team’s biz dev. It’s a way of ensuring you don’t mistake comfort for strategy.

The Evidence of Expertise: A Workbook for Gathering the Facts That Make Your Brand Story Undeniable

Here’s the text of a workbook I wrote. It helps answer the questions: What’s your company done, and why should I trust you?

PREFACE: Why this workbook exists

Most professionals talk about what they believe. Fewer talk about what they can prove.

When a potential client asks, “Why should I choose you?”, they’re looking for evidence: real, specific, repeatable proof that you know what you’re doing and that the results you create aren’t random.

This workbook helps you gather that evidence. You’ll assemble a trail of facts, figures, and stories that prove your reliability, skill, and difference. Every number and every anecdote is a piece of your reputation made visible.

By answering these questions, you’ll build a library of proof points – your evidence of expertise. These ideas can go into your elevator speeches, marketing collateral, sales pitches, and so forth. Don’t feel pressured to complete every question. Some won’t apply to you. Fill out the ones that speak to you.

By the end, you’ll have something few companies ever take the time to create – a living record of credibility that reminds clients, and yourselves, why you’re worth trusting.

TIME AND SCALE

How long have you been doing this work?

What volume of work have you completed?

Across how many industries have you worked?

How many people have you served, directly or indirectly?

Where in the world have you worked?

REACH AND RELATIONSHIP

What recognizable names have trusted you?

What percentage of clients come back?

Which client has been with you the longest, and why?

On average, how long do client relationships last?

What measurable results have clients achieved because of you?

CREDIBILITY AND RECOGNITION

What certifications, licenses, or credentials verify your competence?

What awards or honors testify to quality?

What surveys or ratings confirm satisfaction?

Who endorses you—clients, associations, peers?

Where have your ideas appeared or been cited?

RESULTS AND IMPACT

How much money, time, or effort have you saved clients?

What processes or systems did you improve?

What problems consistently vanish after you’re involved?

What guarantees or promises back your work?

PEOPLE AND PRACTICE

What’s the average tenure of your team members?

What collective experience do they bring?

What training or education do you continually pursue?

What training do you give your clients so results stick?

What materials, technologies, or methods set you apart?

PARTNERSHIPS AND REPUTATION

What partnerships or alliances strengthen your credibility?

Where have your ideas appeared or been cited?

What recognitions, rankings, or listings reinforce your status?

Who outside your company speaks positively about you, and why?

Which client testimonials capture your difference in their own words?

RESEARCH AND INNOVATION

What research or proprietary data supports your approach?

What unique decision-making framework do you apply?

What new technology or tool have you created or customized?

What do you do that competitors rarely attempt?

What principle or method have you refined over years of trial?

STORIES THAT REVEAL CHARACTER

What do clients say you always deliver, regardless of project type?

What story perfectly embodies your defining quality?

What story best captures a moment of recovery – when you made a mistake right?

What story shows loyalty or partnership beyond the contract?

What story reveals your human side—humor, empathy, humility?

VALUES AND BELIEFS

What belief guides you when no one’s watching?

What do you refuse to compromise, even when it costs you?

What personal experience shaped your approach to this work?

What do you believe about your field that few others do?

What legacy do you want clients to associate with your name?

BUILDING YOUR COMPANY SCRIPT

From your library of answers, you can create a short, memorable script your entire company can share, word for word, with pride. Pull the data, facts, and stories that feel most alive. Circle or highlight the ones that sound distinctly like you – not any company, but yours.

Combine them into a confident statement. Think in sentences, not bullet points. Aim for something that sounds true when spoken aloud. It works because it’s not marketing fluff. It’s truth spoken clearly.

Try Before You Buy: The Power of a Sample

This is a strategy you’ve experienced many times. It’s been used on you. Maybe even today. You also may have used it on other people. But I’d hazard a guess you could be using it far more often than you do.

What is this powerful persuasion tool? Let’s call it “sampling.”

The Mr. Peanut Principle

When I was a child, my family took a trip to the boardwalk in Atlantic City. There, in front of the Planters Store, was a man dressed as Mr. Peanut. He was seven feet tall and freaked me out.

Now, Mr. Peanut was standing there, handing out an item. What item?

He wasn’t handing out a Mr. Peanut t-shirt or a Mr. Peanut beach towel. He wasn’t handing out a white paper extolling the nutritional virtue of peanuts.

No, Mr. Peanut was handing out tiny paper bags, each holding seven roasted cashews. Why?

The reason was simple: Planters figured, if you enjoy these seven cashews, you’re in luck. Inside the store right there are pounds and pounds of the very same item. If you like these seven cashews, you’re going to want to go into the store, because you can buy more in there. If you hate these seven cashews, though, you’d better stay out of the store, because there are pounds and pounds of the same item in there, and you’re going to hate it inside.

To me, the Planters strategy was all about ethical persuasion, because there was no separation between the item for sale and the method used to sell that item. They were one and the same. Before buying the item, you could test the item.

To persuade, you need to give people a free or low-cost sample of the thing itself. Or you need to give something as close as possible to the thing itself.

This is true whether what you’re pitching is a product, a service, or an action you’d like an employee to take. You’ve got to ask yourself, “How can the other person try what I’m suggesting in a small, safe way before they fully commit?”

Why Sampling Works

Why is sampling necessary? It’s because of you. People are scared of you. They don’t trust you. They think you might have a hidden agenda. That, or they think you’re aboveboard, but you’re deluded and can’t deliver on what you say you can deliver. Or, what you’re promising won’t work for them.

A sample knocks down those barriers. For the other person, it removes risk. A sample is an principled way of saying, “Don’t guess. Try it. Then decide.”

Sampling in the Digital Age

When you think about sampling, the first thing you probably think of is product samples. We’re inundated with product samples. In the digital age, this has only accelerated.

Streaming Services: Think about Netflix, Hulu, or Disney+. They all offer free trials so you can binge-watch their original content before committing to a monthly subscription.

SaaS (Software as a Service): Most SaaS companies offer a “freemium” model or a limited-time free trial. You can use the basic features of the software for free, and if you want the “professional version” with all the bells and whistles, you can upgrade to a paid plan.

E-commerce: Companies like Warby Parker will mail you five pairs of glasses to try on at home. You keep the ones you like and send the rest back, free of charge. This takes the risk out of buying something as personal as glasses online.

These are all examples of product samples, but you can sample services and even experiences.

Sampling Beyond Products

Coaching and Consulting: Want to hire an executive coach? Instead of committing to a year-long contract, ask for a free 20-minute introductory session to see if the chemistry is right.

Organizational Change: Rolling out a massive, organization-wide change? Don’t do it all at once. Start with a pilot project in one department or team to test the waters and work out the kinks.

Parenting 101: I once heard a story about a school that used sampling to teach teenagers about the responsibilities of parenthood. They gave each student a simulated baby—a doll with a computer inside that would cry at random times and need to be “fed” in the middle of the night. The students had to care for the “baby” for a few days, giving them a very real sample of what it’s like to have a child.

How to Use Sampling

So, how do you put sampling to work for you?

Think about the outcome you’re looking for, and then brainstorm ways to let people experience a small piece of that outcome.

Let’s say you’re a leader and one of your team members is stuck in a rut. Their thinking is stale, and they keep using the same old approaches to problem-solving. You want them to be more innovative, but just telling them to “be more innovative” is a recipe for disaster. It’s too big of an ask. So, you want them to sample what it’s like to think differently.

You could ask, “What’s something small that, just for tomorrow, might help you see things differently?” They might say, “I feel stymied working in my office day after day, staring at the same walls, getting interrupted constantly. If I could do my work in a different environment, that might help me think differently.” You ask, “What’s an environment you suspect might work?” They say, “The coffee shop across town.”

This isn’t some grand leap into innovation, but it’s a start. It’s a taste. You say, “Great. This afternoon, I’d like you to take your laptop and do your work in the coffee shop. See if a new environment changes your thinking at all. Tomorrow morning, stop by my office and we’ll talk about how it went.”

Eureka! They’re now going to go off and sample a new behavior and mindset. They’re not being forced into it. They’re not being coerced. They needn’t buy into it whole hog. Because of that, they’re much more likely to give it a chance, because for them the risk has been reduced.

Your Turn

Now it’s your turn. How are you going to make sampling work for you? Whether you’re in sales, marketing, IT, or a leadership position, think about something important that has to happen, and think of ways that you can give people a sample of the thing itself before they have to buy in. They’ll be much more likely to want to purchase what you’re selling, whether it’s a product, a service, or an idea.

Selling On Truth

A few years ago, my wife and I were in the market for a generator for our house. We had a sales representative from a local firm come over to assess our property. As it turned out, the representative and his father co-owned the company. While he was surveying the land to find a suitable spot for the generator, he asked me what I did for a living.

“I’m a business strategist,” I told him, “but a specific kind. I’m a differentiation expert. I help companies find the idea that’ll make them stand out as different and important when compared to their competitors.”

This piqued his interest, and he asked if he could pick my brain. He started a small side-business selling homegrown hops to local craft breweries and was struggling to find a way to make his product stand out.

When I first asked him why craft breweries would buy his hops, he said it was because they were the best tasting. I thought, “OK, that’s a claim. We can’t use that. Anyone can say that. Also, these breweries already have suppliers with good tasting hops. He’ll need a strong reason to get them to switch from their current sources.”

So, I asked him a different, simpler question: “Why did you start this business?”

His answer was the key. It began as a way to bond with his six-year-old daughter.

He lived on a large farm, and by the time he got home from work, there was little time to play or find projects they could do together. So, he set aside an acre of land to teach her about farming. They decided on hops, a crop that grows quickly and easily. They planted a hundred-foot row, and his daughter loved the experience, watering the plants with her little pink watering can. They planted a second row, and then a third. When it came time for the harvest, he brewed beer with the hops and gave it to his neighbors. Soon after, he and his wife had a second daughter, who also joined in, spending time with her father and older sister on the farm.

I asked him about the farm itself. He explained that it was a 300-acre property that had been in his family for three generations, passed down from his grandfather to his father, and now to him.

“There’s your differentiation,” I said.

I explained to him that many craft breweries are family-run businesses. Even those that aren’t often have a deep connection to their community and the art of brewing. His story would resonate with them. I laid out the narrative he should share:

‘I live on a 300-acre farm. It was my grandfather’s, then my father’s, and now it’s mine. About seven years ago, I put aside an acre to teach my young daughter, Madison, about farming and to have a way to bond with her. We decided to grow hops since they grow tall and quickly. We planted a hundred-foot row. Madison so loved working with me, watering the hops with her little pink watering can and watching them grow, that we planted a second row and a third. When we harvested the crop, I’d brew beer and give it to my neighbors. Madison doesn’t really understand what beer is, she’s never had a sip, but she loves growing the hops with her dad and visiting the neighbors, and giving them the beer as a gift. They so love it that I decided to start a business. My wife and I have a second daughter now, and this gives us a way to work together out in the elements and bond and learn about the family farm."

I advised him to share this story in his conversations with potential clients. I suggested he put it on a website with photos of his family on the farm. I also recommended he create a PDF of the story to send to breweries before meeting with them.

In a world of polished marketing messages and carefully crafted brand identities, the simple, unvarnished truth can be the most powerful differentiator of all. Your story, in its most authentic form, is your sale.

The Box That Didn't Care What I Thought

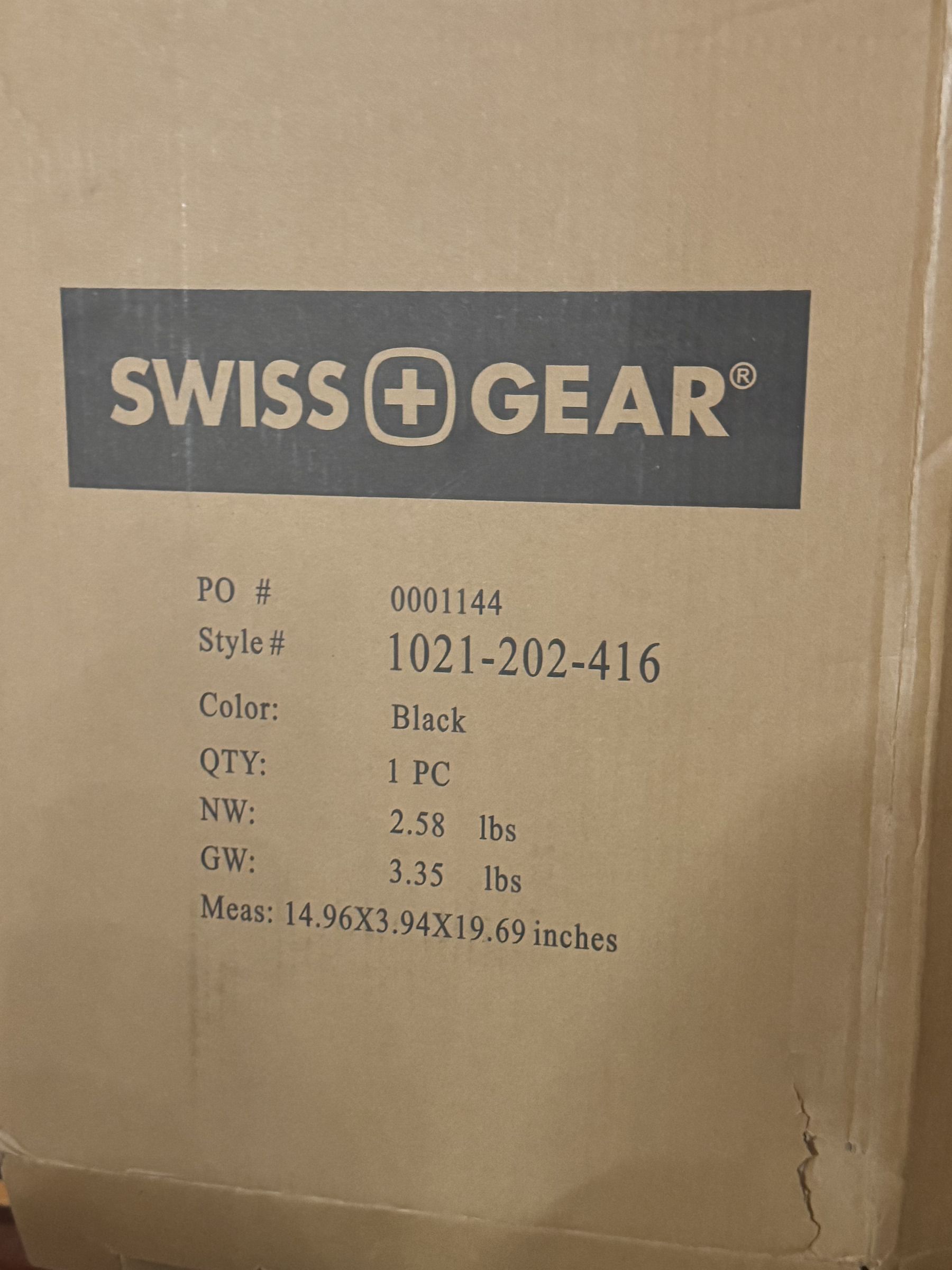

For Christmas, my wife bought me a SwissGear backpack. Before I even took the backpack out, its box caught my attention. Not because it was attractive or clever, but because it was aggressively uninterested in me.

Printed on one side of the box were the familiar details of logistics: PO number. Ten-digit style number. Quantity. Net weight. Gross weight. Measurements to the second decimal place. It was inventory and warehouse language, pure and simple. I could almost hear the beep-beep-beep of a tractor-trailer backing up to a loading dock, ready to off-load skids.

But then I turned the box over and found a subtle, yet profound, variation. While most of the information was identical – the PO number, the style, the color – the weight details were replaced with something else: “Carton # ___ of ____.”

This wasn’t just a blank space. The second number, 290, was printed, a clear indicator of a vast shipment. But the first number, 38, was handwritten in black marker. A distinctly human touch on an otherwise sterile container.

This small detail amplified the box’s core message. The box wasn’t telling a story; it was refusing to tell one. The handwritten “38” wasn’t for me, the end consumer. It was a mark of process, a note from one part of the system to another. It conveyed an even greater, more fascinating indifference. It was as if a worker on the line noticed something, made a mark, but the line never stopped moving. The system acknowledged a human was there, but only as another functional part of the machine.

The message the box conveyed was blunt: this is one unit in a system. This is carton 38 out of 290. The system does not care whether you’re paying attention. It will work anyway.

If you take that posture seriously, it starts to imply something more specific. SwissGear isn’t saying, “Look how carefully this was made.” They’re saying, “Here is one unit moving through a machine designed to handle millions of units without drama.”

And oddly, that restraint—that raw, unadorned display of process—creates confidence.

Which raises a harder question. If someone stripped away your company’s language and left only the system underneath, would it hold up? Or are words doing more of the work than the machinery beneath them ever could?

Why Samuel Adams’ “Illegal” Beer Isn’t a Mistake

Recently, Samuel Adams released the latest version of its Utopias beer, a limited edition that clocks in at roughly 30 percent alcohol by volume – about four to five times the alcohol content of a conventional beer.

Utopias is sold in a ceramic bottle for around $240, is produced in very small quantities, and is illegal to sell in roughly fifteen U.S. states because of its elevated alcohol content.

At first glance, that looks like a business error. A third of the country can’t legally buy your product? A conventional strategist might reasonably ask, “What were they thinking?” But that reaction misunderstands the logic.

Samuel Adams has been releasing versions of Utopias every couple of years since the early 2000s, and with each release the alcohol content has increased. That escalation isn’t accidental. It’s the strategy. Making a beer so strong that it crosses legal thresholds isn’t a regulatory problem to be managed.

It’s the story.

Once the bottles sell out, which they reliably do, the effect lingers. People who will never taste the beer still carry the association. Samuel Adams makes a beer so extreme it’s banned in parts of the country! That idea lasts far longer than any campaign.

What counts here isn’t shock value. It’s which part of the product the brand chooses to push.

Beer is, at bottom, about alcohol. Sure, taste, craft, and ritual all play a role. But people buy beer because it does something to them. When Samuel Adams cranks the alcohol up, they’re not bolting on a gimmick. They’re leaning hard into the very reason beer exists.

That’s why this strategy works.

If the oddity were incidental, it would feel wrong. Imagine Samuel Adams releasing a beer bottle that dissolves after opening, or one with a label made of sandpaper, or a cap that requires special tools. Those might be memorable, but they’d be arbitrary. They wouldn’t deepen what beer is for. They’d pull attention away.

That difference shows up in plenty of other products as well.

Strong positioning pushes harder on the thing the product already does for people. Weak positioning adds drama somewhere else and hopes it sticks.

Once you see that, the pattern is easy to spot. With beer, you push alcohol. With coffee, alertness. With air conditioning, cold delivered fast. With a hotel, rest or silence. With consulting, resolution. With software, speed or focus. The principle is the same every time: exaggerate the reason the product exists, not the decoration around it.

Many companies push what’s easiest to dramatize rather than what actually defines them. They ask, “What will get attention?” instead of, “What is this business truly for?”

If you’re going to push something to the edge, push the reason the product exists. Do that, and even the people who opt out will understand what you stand for.

Five Questions to Test If Your Strategy Is Real

What follows is a short diagnostic to help you tell whether your strategy has crossed that line, from something people understand intellectually to something they can actually recognize in their day-to-day work.

A Strategy Recognition Test

Answer these questions honestly and without overthinking them. If you find yourself hesitating, that hesitation is useful information.

- Can someone describe the strategy without using your words?

If people repeat leadership language verbatim, it often signals compliance rather than understanding. The real question is whether they can translate the strategy into their own terms.

A simple test is to ask a few people in different roles to explain the strategy to someone outside the organization. If their explanation collapses into abstractions or jargon, the strategy hasn’t yet entered their thinking in a usable way.

- Where can someone experience the strategy today?

This isn’t about hearing a description of the strategy. It’s about encountering it in action.

Is there a pilot team, a prototype process, a changed customer interaction, or a part of the organization where the future state is already operating, even in a limited form? If there’s no place where someone can see the strategy being lived, you’re asking people to move toward something they can’t yet recognize.

- What familiar behavior does the strategy amplify?

Effective change rarely starts from zero. It usually builds on something people already value or do well.

What existing habit, value, or behavior does the strategy make more visible, easier, or more frequent? If the strategy requires people to abandon everything they know and start over, it’s likely to stall. Change needs an anchor in what already feels familiar.

- Who has already lived the future?

This isn’t about who approved the strategy or endorsed it in principle. It’s about who has actually operated under the new model long enough to speak from experience.

If no one can point to firsthand experience, the rollout is asking for belief rather than providing evidence. Leaders don’t need to demand trust when they can offer proof.

- What would still look different if the strategy were ignored?

This question combines two important tests.

First, if someone asked, “What has changed?”, what would people point to? Real change shows up in concrete things: decisions made differently, behaviors that have shifted, moments that stand out. If the answers are slides, slogans, or meetings, the strategy hasn’t yet crossed into daily work.

Second, imagine a new hire joining tomorrow who pays no attention to the strategy deck. What would they still notice was different about how work gets done? If the honest answer is “not much,” then the strategy hasn’t yet altered the environment.

Until the environment changes, behavior usually won’t.

The Telling Conclusion

Most strategies don’t fail because the direction was wrong. They fail because people didn’t know what it meant for them, day to day.

If even one of these questions made you uneasy, that’s useful. It points to where attention is needed next.

The Strategy Was There. They Just Didn’t See It.

I don’t know if the story you’re about to read is literally true. It may be a business parable that’s been passed around long enough to feel historical. I’ve seen versions of it attributed to Arie de Geus, and I was reminded of it while rereading “The Art of the Long View” by Peter Schwartz.

Whether it’s fact or fable, the point it makes still holds.

In the early twentieth century, a group of British scientists encountered a tribe on the Malaysian Peninsula that had little contact with the modern world. The tribe was so isolated that it had yet to invent the wheel. The scientists invited the tribe’s chief to travel with them to the nearest modern city, Singapore, so he could see the latest wonders.

For a day, they showed the chief what they assumed would be astonishing: tall buildings, elevators, electric lights, locomotives, machines. Then they brought him back to his village.

When they asked what had made the biggest impression, the chief didn’t mention the buildings or the locomotives or electricity. Instead, he said he’d seen a man carrying more bananas than anyone in his tribe could carry. How? The man from the city was carting a pile of bananas in a wheelbarrow.

The key to the story isn’t the wheelbarrow, however. It’s the bananas.

The chief already had a mental category for bananas. His civilization had bananas. He could relate to gathering them, carrying them, needing them. The wheelbarrow made sense because it amplified something he understood already. The rest of the city, electricity, locomotives, infrastructure, fell outside his field of experience. It was as if they hadn’t been there at all.

We don’t see what we’re not prepared to see. This is where most strategy rollouts go wrong.

Leaders assume that if they explain the strategy clearly enough, people will get it. They build PowerPoint decks, write memos, hold town halls. They describe the future in words and diagrams, then wonder why nothing changes.

What’s actually happening is simpler and more uncomfortable. The strategy lives outside people’s existing conceptual categories. So it doesn’t register. It isn’t debated or resisted. They just don’t see it. People can’t move toward a future they can’t recognize.

That’s why one used car dealership transformation worked when so many don’t.

I first came across this example in writing by Larry Johnson. A son inherited his father’s car dealership, a classic hard-sell operation where customers were treated as transactions to close. The son hated that “Always Be Closing” model. He wanted to shift the entire business to a human-friendly, customer-first approach.

He didn’t start by rewriting the strategy or lecturing the staff. Instead, he sent his managers to customer experience training run by the Ritz-Carlton. The managers came back changed. They had experienced a completely different operating model. They had seen what customer-first looked like when it was real, not aspirational. When they returned, implementing the strategy became dramatically easier, because people weren’t being asked to imagine a future. They had visited it.

This is the real work of strategy rollout.

If you want people to adopt a new strategy, you have to help them see it, not just hear about it. That might mean a pilot project, a prototype, a shadowing experience, a visit to another organization, or a lived demonstration of the future state.

This isn’t about motivation or compliance. It’s about preparation. Until people have a mental handle for the new direction, the strategy goes by like electric lights and locomotives. Not actively shunned. Just unseen.

If You Can't be Named, You Won't be Called

Years ago, I wanted to write for the Sunday New York Times Book Review. An editor there liked my writing and offered to give me a chance. On the phone, he asked what kind of books I reviewed.

I thought the honest answer would impress him. I had been a director at a large book wholesaler, and had helped them sell over a billion dollars’ worth of books. As a part of my job, then, I had a working knowledge of nearly every book on the market.

So I said, “I review any type of book.” I was waiting for excitement. Maybe even awe. Instead, there was a pause.

Then the editor spoke to me with great sarcasm, slowly, as if I were four years old: “Mark, I have an index card here with your name and address on it. There’s a spot at the top for me to write the type of book you review. If I write ‘Reviews any type of book,’ I will never call you. Do you know why?” I didn’t.

“Because publishers don’t publish books in the category of ‘Any type of book.’”

At least I was quick on the uptake. I asked him what kinds of books he had the fewest reviewers for.

He paused, gathering a list in his head. “Sports and . . . “

“Stop,” I said. “I review sports books.”

And just like that, the totality of me was reduced to one thing. Sports books. Not because it captured everything I knew, but because it fit on the card. It gave him a reason to remember me and a reason to call.

Once you notice this kind of reduction, you see it everywhere.

The other day, I was in a pizza place. A waitress was talking to a woman about a former boyfriend. She referred to him as “the lasagna guy.” Later, two customers nearby were talking. One mentioned his son and called him “a baseball kid.”

This is how people think and talk in the wild.

The full complexity of the boyfriend was compressed into his love of lasagna. The entire inner life of the boy was shrunk down to baseball. There was no cruelty in it. No nuance either. Just fast shorthand.

This is how buyers think, too.

They don’t slowly assemble a complete picture of your company, or hold your full range of capabilities in their heads. They grab the first usable handle they can find, and they use that to decide whether you’re relevant and worth another conversation.

Understand that I’m not arguing for reduction as a virtue. All I’m say is reduction happens whether you like it or not.

Which is why the distinction between pigeonholing and positioning is important.

Pigeonholing is what happens when someone else does the reducing for you. Positioning is when you decide, in advance, which reduction you’re willing to live with.

The mistake I made with the Book Review was thinking that breadth was impressive. In business, breadth is usually invisible. Specificity is what gets you called back.

Good positioning doesn’t try to describe everything you do. It chooses the thing people can name. The thing they can repeat to a colleague. The thing that fits on the metaphorical index card.

Clear Enough to Obey

Before Richard Webster became one of the most prolific writers alive, with well over a hundred books to his name, almost all of them written long before AI was even a rumor, he was something else entirely: a magician and mind reader from New Zealand who wanted to be a writer and had written very little.

Webster admired many authors, but he was especially awed by “Call of the Wild” writer Jack London. Not just London’s stories, but his literary output. London died at forty and, in that short life, produced dozens of books along with hundreds of short stories, essays, and articles. The sheer volume felt almost superhuman.

On an early trip to the United States, Webster made a pilgrimage to London’s home in California. On the wall hung a list of London’s rules of work. One of them was brutally plain: write one thousand words a day.

Webster did the math. Follow that instruction and you could finish a book in a couple of months. Keep going and you could write several books a year. When he returned to New Zealand, though, something noteworthy happened.

Webster had misremembered the rule. Instead of writing a thousand words a day, he began writing two thousand words a day, day after day after day.

When Webster discovered his mistake decades later, it was irrelevant. His misremembered two thousand words a day rule had already turned him into a literary machine.

What made it work was not precision. It was that the instruction was clear enough to obey. It was something Webster could execute even on bad days, when inspiration failed him. Following the instruction didn’t promise greatness. Rather, it gave him direction and forward motion.

That’s also why people love challenges and games. They remove ambiguity. They replace “What should I do?” with “Just do this.”

I’ve run into the same principle in a very different corner of my life. I spend time visiting abandoned buildings, forgotten memorials, and historical oddities, places that often take real effort to reach and offer very little at first glance. On one trip, I drove deep into the New Jersey Pine Barrens to find a small monument marking the crash site of Emilio Carranza.

Carranza died in 1928 at the age of twenty-two. In Mexico, he was already a national hero. That year, he flew nonstop from Mexico City to Washington, D.C., as a symbolic gesture of goodwill between the two countries. After meeting with Calvin Coolidge among others, Carranza began the return flight south. He never made it. His plane was caught in a violent nighttime storm and went down in the Pine Barrens’ dense forest.

After hours of driving and searching, I finally reached the monument site. Yet when I got there, I felt almost nothing emotionally. There was no click. I looked around for a few minutes and was ready to leave. The place seemed quiet and unremarkable.

Then I reminded myself of a rule I use deliberately in moments like this. I say to myself: “Mark, at some point you thought coming here would be worth it. Why did you think that? Assume you were right. What did you know then that you’ve forgotten now?”

So I stayed. I studied the monument and the surrounding trees more closely. I pulled out my phone and began researching details prompted by what I was seeing rather than what I already knew.

I learned that Carranza had taken off from Garden City, that when his body was recovered a flashlight was fused into his hand, suggesting he had been flying low over the treetops, trying to find a place for an emergency landing in an aircraft not designed for night or weather. I learned that schoolchildren in Mexico had pooled their money to help fund the memorial in a remote corner of the New Jersey woods.

Only then did the place begin to feel meaningful.

I think about that moment when I’m tempted to leave too early, whether it’s a place, a piece of writing, or a line of thought. Not everything rewards assiduous attention. But some things do, if you stay just a little longer than feels comfortable.

Webster had an instruction that was clear enough to obey. So did I. Neither instruction was elegant. Both helped us get the job done.

What Would Give Me the Right to Tell This Story?

When they want to make a point, many people look for a story to illustrate it.

They think, “I want to talk about persistence, so let me find a persistence story.” And they end up telling the same story about Lincoln’s long string of failed campaigns and political setbacks that everyone else tells.

The problem with that approach is that it’s deductive storytelling. You’ve chosen the moral first and then gone hunting for a story that fits. That leads to hearing the same tired stories over and over again. You’re just borrowing from work that’s already been done.

I teach leaders and speakers to do the opposite. I tell them to start with the story that fascinates them and then ask, “What would give me the right to tell this story? How could I earn it?"

In other words, what does this story teach me or reveal to me that I didn’t see before? What’s the part of the story that never makes it into the headline, but changes how I see it?

That’s the difference between inductive and deductive storytelling. But I don’t think of it in those terms. I think of it as letting the object lead. The story is the object. You don’t impose a lesson on it. You let the lesson emerge from it. You let it show you what you didn’t know.

This approach is not really a technique. It’s more a way of living. You keep your eyes open for stories you’d want to tell, whether you know why or not, and you hold onto them. Later on, you figure out why they’re important to you, and that importance becomes the lesson.

By the way, an outgrowth of this approach: a writer named Lou Willett Stanek once wrote, “Stories only happen to the people who can tell them.” So as you go looking for stories, you start seeing the world in stories.

True Stories No One Asked For

I found a document I’ve kept since 2009.

It’s only a few pages long, and I’ve rarely opened it. I didn’t keep it faithfully or systematically. And yet, somehow, these stories found their way into it. I’ve changed some names.

What follows is that document, lightly edited and rearranged.

◦

Dan told me a story from his life as a police officer.

A woman said it had been days since she’d seen her neighbor, Henderson. Dan went to Henderson’s apartment for a wellness check. No answer. He broke in and found Henderson’s body on the floor, bloated and decomposing.

It was the middle of the day, the sun was shining brightly, but the apartment looked like the dead of night inside. The windows were thickly covered with houseflies, blotting out the light.

◦

Lena told me about her Uncle Ray, who has shrapnel embedded under one eye.

Fifteen years earlier, Ray had been carjacked in Los Angeles and refused to hand over the car. He told the carjacker the car wasn’t his, it was a rental, so he couldn’t give it away. The carjacker shot him in the face.

The carjacker took Ray’s wallet. Inside was a tattered piece of paper Ray had written himself, covered with single words. He called them “joke starters.” Each word was a prompt that jogged his memory for a specific joke. He’d glance at a word like linguini and launch into the one that went with it.

At family gatherings, the kids would crowd around him asking for jokes. By the fourth or fifth joke, they’d wander off bored.

After the carjacking, Ray started a new joke-starter paper.

◦

I saw a news story about an attempted armed robbery.

A 22-year-old gunman entered a check-cashing store, jumped the counter, and pointed a gun at the only employee, a woman who immediately began crying and praying out loud.

The gunman panicked, dropped the gun, and prayed with her. They hugged.

Then he handed her the gun’s single bullet, left the store, and turned himself in.

◦

I watched an ABC News video that played a 911 call.

A seven-year-old boy had locked himself and his little sister in a bathroom while three armed men held their parents at gunpoint in another room. The boy called 911. The dispatcher told him police were on the way.

The boy said: “Send soldiers, too."

No one ended up being seriously hurt.

◦

At the gym, Mara told me that when she was a kid, her parents took her to a casino and gave her a few coins to play the slot machines. On her first coin, she hit a jackpot. Her father told her to quit. She tried a second coin and hit another jackpot.

Mara’s mother gambled rarely. When she once hit a slot-machine jackpot herself, the flashing lights and clanging bells frightened her. She thought she’d broken the machine and fled the casino without collecting her winnings.

◦

I was sitting in Clinton Bagels when two tough-looking workmen came in wearing jeans, flannel shirts, tool belts, and baseball caps. They sat down for lunch.

About fifteen minutes later, a third man walked in from the parking lot, spotted them, and said, “Hey, you guys get a new truck?”

One of the tough-looking workmen said, “Same truck. New decals.”

◦

Erin was thinking about taking a trip to Egypt.

Caleb, who liked to joke while keeping a completely straight face, told her that five weeks earlier a group of mystics near one of the pyramids had held a ceremony and brought a mummy back to life.

“The mummy pushed someone,” Caleb said, “and took their suitcase.”

Erin asked, earnestly, “Really?”

◦

Stella finished eating her Chinese takeout and broke off a piece of fortune cookie for our Shiba Inu, Jofu.

As she bent down to feed him, the paper fortune slipped off the countertop and fell to the floor. Jofu ate that too.

The fortune had read, “A small gift will please the whole family.”

◦

I was writing in a WORD document and misspelled the name of the famed German philosopher, Heidegger.

Spellcheck suggested I change it to “Headgear.”

◦

A stink bug climbed the side of Stella’s soda glass.

Stella hates looking at bugs, but she also doesn’t like killing them, for ethical reasons. As she tried to shoo the bug into the kitchen sink, she said, “Get out of here, you stupid loser.”

Minutes later, our cat Jinx sneezed directly into Stella’s arugula salad. She threw the salad into the garbage.

◦

After his long run with the San Francisco Giants, outfielder Hunter Pence published a farewell note to the fans who had treated him so well. He opened with the following line:

“I definitely wish some of the greatest times in our lives could go on forever and somehow, I believe they do.”

Begin With Your Conclusion

Let’s start by giving away the punchline: When you speak or pitch or write, begin with your conclusion.

I originally learned this strategy from Edward Bailey’s “The Plain English Approach to Business Writing.” There’s nothing fancy about it. It’s almost offensively simple. And it works. Here’s what I mean.

Imagine someone from your department walks into your office and says, “I have something important to tell you.” You put aside the five things you’re working on. He continues:

“The other day I was in Manhattan. I was eating at a restaurant in the theater district, and I saw a friend I hadn’t seen in years. His name is Ricky. He’s a big-time lawyer now. So Ricky comes over to my table, I’m eating eggplant parm, and we start talking about old times. Something he says, though, triggers a memory from when we were in high school . . . ”

Let’s pause there.

If you were listening to this, what would you be thinking? Me? I’d be thinking: Manhattan. Ricky. Lawyer. Eggplant parm. Got it. Why are you telling me this?

If he keeps going, you get antsy. Then irritated. And here’s the important part: even if what he has to say is genuinely important, you have no way of knowing that yet. Why? He won’t tell you what he’s asking of you! So part of you just wants him to leave. We’ve all been on the receiving end of this. And if we’re honest, most of us have done it ourselves. Why does it happen?

One reason is that we present information the way we experienced it, instead of the way someone else needs to hear it. We’re asking the other person to do all the work of figuring out what matters.

Another reason is fear. We’re afraid to say the point up front. We worry the other person will judge it too quickly, or won’t understand how we got there. That fear feels prudent, but it isn’t. Hiding the point doesn’t make rejection less likely. It just makes the conversation harder to follow and easier to dismiss.

So try this instead: start with the conclusion, or the recommendation, or the main idea. Then explain yourself. It sounds like this:

“Hey, I think we should ask for a ten-day extension on this deadline. Here’s why.”

Or: “Instead of going to Florida this year, I think we should go to South Dakota. Here’s why.”

Now the listener knows what game they’re in. They can follow along, and agree or disagree. But they’re not guessing why you’re talking.

Looy on Grippo

While researching an article on Las Vegas magic in the late 1990s, I asked my friend Looy Simonoff about the colorful close-up magician Jimmy Grippo (1898–1992).

For the next two hours, Looy told me one Grippo story after another, each more extraordinary than the last. What follows are my notes from that conversation. They’ve been lightly edited for clarity and order, not substance. The stories, opinions, and judgments are Looy’s as I recorded and remember them. Any errors are mine.

—

Grippo had an unusual look about him. He had a glass eye, and he’d tell exotic stories about how he lost the real one. In truth, it happened when he was a kid, from a firecracker.

When Grippo was in his twenties, he had a fancy glass eye made, with diamonds around the iris. He’d take the eye out and ask someone to stare at it while he was trying to hypnotize them. As strange as that sounds, the eye wasn’t the most curious thing about his appearance. That was his hair.

Grippo always wore an obvious wig. It was jet black, thick, and combed into bangs all around his head. He wore this jet black wig even when he was very old. When I went to visit him in the hospital after his stroke, I saw the wig hanging on a hook by the bed. The funny thing was that his real hair looked almost exactly like the wig, only a little thinner on top.

That same stroke left Grippo’s left hand paralyzed, at least for a while. When he eventually regained movement in the hand, he didn’t tell anyone. Instead, he continued doing tricks with his good right hand, while his supposedly paralyzed left hand stole things and helped with secret loads.

Grippo’s reputation was built largely on challenges. He’d start a trick, look at the spectator, and say, “Now how do you want this to end?” The spectator would challenge him with something like, “Make it come out of my pocket,” or “out of my necktie.” And Grippo would do it.

I remember hearing about one time when Grippo and his friend Joe Condon walked into a jewelry store just as it was closing. The proprietor was on his knees by the open safe, counting the day’s receipts. Without hesitating, Grippo secretly scaled a playing card over the man’s head and into the safe just as it was being closed.

Condon then introduced Grippo to the proprietor, who said, “I hear you do great card magic.”

“Well, I try,” Grippo said.

Grippo then forced a duplicate of the card he’d already tossed into the safe. After that, he said, “Challenge me. Make me produce your card in some hard place.”

The proprietor said, “My pocket?”

“No,” Grippo said. “Real hard.”

The proprietor thought for a moment and said, “Can you make it appear in that safe?”

Grippo replied, “Well, I don’t know about that . . . ”

Grippo also used to do a challenge involving money. He always carried large amounts of cash and would bet people that he was carrying more money than they were. He always won.

One day, though, a big-shot gambler decided he was going to beat Grippo. The gambler had about twenty thousand dollars on him and went looking for Grippo. Unfortunately for the gambler, he bragged about it beforehand to Dai Vernon. Vernon tipped off Grippo, which gave Grippo time to prepare.

When the gambler finally found Grippo, he said, “Beat this,” and pulled out the twenty thousand dollars.

Grippo looked perplexed, then slowly began pulling crumpled bills and coins out of his pockets. About half an hour later, he finished by producing just enough money to beat the gambler.

Grippo was also a very good hypnotist. He used hypnosis in a weight-loss clinic in Florida to help elderly patients lose weight. He told me that whenever he got out of his car down there, crowds of overweight elderly people would gather around him, asking to be put under.

He also performed mock hypnosis stunts. You know the trick where you apparently cut your thumb and produce great amounts of blood before it heals up? Grippo did a variation of that trick when performing for doctors. He’d tell them he was hypnotizing himself, but instead of cutting his thumb, he’d apparently cut his throat. It looked terrifying. Then he’d make the wound “heal.”

At one point in his career, Grippo developed a tolerance for electric shocks and began using them in his hypnotic act. He concealed a Tesla coil on his body, took a spectator by the hands, and commanded the person to kneel. If the spectator resisted the hypnotic suggestion, Grippo would activate the coil and, using his own body as a conductor, shock the spectator into dropping to the floor.

He stopped using the coil when he learned it was causing him heart arrhythmia.

Grippo also managed prizefighters. The character Evil Eye Fleagle in the “Lil’ Abner” comic strip, who put hexes on opposing boxers, was modeled after him.

Grippo would stand ringside, staring at a boxer and waving his hands, apparently putting a spell on them. Later, he hypnotized Muhammad Ali and told him he was invincible. He also taught Ali magic.

Grippo was always telling stories, and every so often, one of the strangest ones would turn out to be true, which meant you never quite knew what to believe.

For example, he used to claim that he’d advised Roosevelt to call his radio talks “fireside chats.” That sounded implausible.

But Grippo also had a photograph of himself in the Oval Office, sitting at the President’s desk, with Jimmy Carter and Walter Mondale nearby, standing.

Confusing a Rule With a Goal

Years ago, I took a short standup comedy course in Manhattan. It ran for about three weeks, meeting twice a week. We wrote material, then performed it for the class in an old classroom.

At the end, there was a kind of final exam: five minutes on stage at Caroline’s on Broadway, the same club where Jerry Seinfeld, Louis C.K., Chris Rock, and Norm Macdonald had worked.

I was terrified. This was before I became a professional speaker. I wasn’t worried about bombing so much as freezing. Forgetting my jokes. Standing there unable to speak.

I went to see my comedy teacher, Stephen Rosenfeld, during office hours. He listened and said, “That’s perfectionism.” Then he gave me an analogy I’ve never forgotten.

He said perfectionism is like insisting you drive from Manhattan to Cape Cod without making a single left turn. (Manhattan and Cape Cod are 250 miles apart. On a good day it’s a five-hour drive.) “What does not making a left have to do with getting to your destination?” he asked. “Nothing. If you want to get to Cape Cod, make as many left turns as you need.”

What struck me later was how easily we add a needless rule to what we’re doing and then treat it like a design requirement. As if the goal were “don’t make mistakes,” instead of “get to the place you want to go.”

Rosenfeld told me he’d seen performers give technically faultless sets that moved no one. And he’d seen others go on stage, forget their lines, pull notecards out of their pockets, shake, cry – and the audience loved them.

“You can give a strong performance while making mistakes,” he said. “Perfection isn’t necessary. It’s not even possible.”

What's Your Parlor Trick?

If you mention you’re a magician, you’re not asked for an explanation. You’re asked for a demonstration. “Let’s see a trick.”

That’s because magic is a demonstration business. You can’t just take someone’s word for it. Without a demo, there is no magic. You’re just making a claim. You have to prove yourself right then and there, with no time to prepare.

That idea, giving people an impromptu experience of your abilities, shows up all over my work as a differentiation consultant and business strategist. It’s why I often give clients an exercise I created called “What’s your parlor trick?” or sometimes, “What’s your Houdini trick?”

I ask them this: Suppose you’re at a party and you meet someone who could be critical to the future of your business. An important stranger. What could you do in five minutes that would give that person a visceral understanding of how good you are at your job?

Not a pitch. Not a résumé. An actual, on-the-spot demo. Something that makes them say, “Oh, wow. Now I get it.”

In other words, what small business-related miracle could you perform at the drop of a hat?

I once asked that question of a client who specializes in subscription models. So I tested her. I’d name a business. Any business. A manufacturer. A bicycle rental shop. A yoga studio. A niche software company. She’d pause for a beat, ask one or two precise questions, and then talk. In a few minutes, she’d lay out a subscription model that made the business feel crystal clear. Why someone would join. Why they’d stay. What would make it hard to leave. You could hear the logic click as she spoke.

That, repeated across wildly dissimilar businesses, was her demo.

Later, when it came time to write her books, the instinct wasn’t to explain subscription models in the abstract. It was to recreate that experience on the page. The range of examples came directly from those conversations. You could hear her thinking at work the same way you could when she was doing it live.

Most people try to explain why they’re good at what they do. Magicians know the explanation comes second. First, you show.

And the parlor trick is usually smaller than people expect. It’s often the thing you do so easily you don’t think it counts. Or the thing people keep coming back to you for. Or the part of your work that feels almost playful, which is why you’ve never formalized it. Those are usually the clues.

If you can’t do a small miracle in five minutes, it’s hard for people to believe in a bigger one later. And if you can, you don’t have to convince anyone of anything. Your parlor trick does the talking.

End Brake Retarder Prohibition

I’ve never in my life seen a four-word sentence made up entirely of constraining words. Then I noticed a traffic sign near my house: “END BRAKE RETARDER PROHIBITION.”

I love that phrase because it feels like an Easter egg I wasn’t meant to find.

End.

Brake.

Retarder.

Prohibition.

Every word is about stopping, slowing, restraining, or forbidding. It’s a sentence bursting with friction.

What makes it even better is that the sign appears as part of a two-sign sequence. A hundred or so yards earlier, there’s an initial traffic sign that reads: “BRAKE RETARDER PROHIBITION.”

So this first sign says no. The second sign says the no is over. And somehow the most restrictive-sounding sign of the two is the one that restores permission. Too cool!

When I looked it up, I learned that the phrase End Brake Retarder Prohibition is perfectly clear to the people it’s written for (truckers). It does exactly what it’s supposed to do.

I know I’m not the audience, and that’s part of the joy. It feels like I’ve stumbled across a sentence that escaped from a world I was never supposed to know about. Like it’s a gift.

Keep Your Slogan Simple

High up on a wall in my neighborhood gym, there’s a sign that reads:

“What Doesn’t CHALLENGE You Won’t CHANGE You.”

It’s the only permanent sign inside the gym, so you’d guess its message is important. It’s one whose wisdom the gym owners want stamped into people’s minds. And it’s painted in giant letters.

Which makes what comes next even stranger.

Gym-goers walk past that sign all day long without noticing it. Trust me, I’ve asked. Of the ten people I’ve quizzed, seven didn’t realize a sign was there at all, and the other three couldn’t recall what it said. (One did say, “It’s something about challenging yourself.”)

How could such a big sign be so invisible?

The sentence is loaded up with the negatives “doesn’t” and “won’t,” which slows comprehension down. The real problem isn’t the negatives themselves. It’s that the sentence has to be mentally flipped into a positive before it makes sense. That’s asking way too much.

What could the sign have said that would’ve been easy to absorb while you’re panting between sets? Here are a few that wouldn’t need conceptual translating:

No challenge, no change.

Struggle builds strength.

This is supposed to be hard.

Discomfort’s the point.

This is how folk wisdom catches on. Not because it’s smarter, but because it’s sayable. Everyone knows the idea behind “What you focus on grows.” But imagine if it had arrived as, “What you do not focus your attention on will not meaningfully improve for you.” Same idea. Dead on arrival. Wisdom spreads when it can be carried easily, especially by tired, distracted people. If it needs translating, it doesn’t travel.

There’s a reason slogans are simple. Nike didn’t say, “Consider the possibility of action.” They said Just Do It. Apple didn’t say, “We value creativity and nonconformity.” They said Think Different. Mel Robbins didn’t say, “What you don’t need to control in others won’t ultimately affect your well-being.” She said, Let Them.

Simple language sticks. If the message matters, make it impossible to miss – especially if your reader has just done five sets of box jumps.

33 Questions to Business Differentiation

Years ago, when I first started speaking professionally, friends told me I needed a lead magnet after my talks. Something simple. So I wrote this brief guide. At the end of a speech, then, I’d tell the audience that if they wanted a digital copy of “33 Questions to Business Differentiation,” all they had to do was hand me their business card and I’d send it along.

And damn if the guide wasn’t good! You really can uncover a true point of differentiation by following the advice and answering the questions. More than one person has told me that a single question in this guide changed how they talk about their business.

33 Questions to Business Differentiation

In the world of business, standing out isn’t an option. It’s essential. If your offering sounds like thousands or even millions of other offerings, you’re not giving the market any reason to choose you over your competitors.

To make your offering a success – be that offering a consulting project, product, service, book, or speech – your work needs to come across to the market as not just good, but different. What’s more, that difference can’t be trivial. It must have substance.

To help you create significant differentiation for your firm, or for any one of your offerings, I’ve compiled a list of questions that may lead you to the differentiation you’ve been searching for.

Using the list

Below, you’ll see 33 questions. Don’t try answering all of them at once. As a matter of fact, you may only need to answer a few. What you should do is this:

Read through the list. One question will jump out at you. That is, when you read it, you’ll feel the itch to answer it. Go ahead. Answer it.

Open your computer to a blank document or take out a pad and pen. Spend as little or as much time answering the question as you’d like. I’ve seen people take as little as a few seconds or as much as forty minutes to answer a single question.

When you’ve answered that question, again scan the list and see which question intuitively hits you next. Answer that new question. And so on. Keep going.

After an hour or so, put the list away and come back for another session later in the day, or even a few days later.

Once you’ve put in significant work, read over everything you’ve written and underline any ideas, words, phrases, and stories that strike you as promising. Does a single differentiating idea stand out, or can you string together a series of thoughts that lead to a differentiating idea?

If yes, think about all the ways you can use that idea to differentiate your firm and thought leadership pieces. If not, keep answering questions until a differentiator appears.

If you haven’t discovered a differentiator on your own, call upon a small group of your most trusted advisors, and share the best pieces from your written exploration. These advisors might help you see that you’ve already created a differentiator of potential.

A final note: On the list you’ll notice a few questions with a negative slant, such as “How might some of your pet business ideas be wrong?” The reason? I’ve found that when we approach a problem-solving situation from one vantage point only, we get stuck. By thinking about what we don’t like and where we might be wrong, we create room in our minds to mull over interesting ideas we wouldn’t have considered before.

The 33 Differentiation Questions

• Why did you begin your current business?

• Who is your ideal audience?

• How is your ideal audience different from other audiences?

• What can a member of your ideal audience do once you’ve worked with them that they couldn’t do before?

• What does your ideal audience need to hear from you most?

• What makes you the perfect person to deliver your work?

• What about your work is obvious?

• What about your work is surprising?

• Who admires your work, and why do they admire it?

• Whose work do you admire, and how have they influenced you?

• What business ideas do you most envy?

• What client problems do your competitors solve that you don’t?

• What are your pet business ideas, and why is each important to you?

• How might some of your pet business ideas be wrong?

• How does your work make a difference to others?

• How does your work make a difference to you?

• What part of your business do you most enjoy?

• What part of your business do you hate?

• What moments in business have made you most proud?

• What moments outside of business have made you most proud?

• What are your favorite business stories?

• What is the worst advice about your topic you’ve ever heard?

• What do you know about your topic that others don’t know?

• What do you know about your topic that others may know, but haven’t thought to say?

• What obstacles have you overcome?

• What are your weaknesses, and how might they be turned into strengths?

• Where in business have you shown courage?

• Where outside of business have you shown courage?

• What two changes would make the biggest difference to your business?

• What part of your work is underappreciated?

• What part of your work brings the most compliments?

• What is the greatest work-related compliment you’ve ever received?

• Over the next three years, if you could only teach your audience about one idea, what would that idea be?

The Existential Close

I created a sales technique called the existential close.

Now, I hate sales techniques. At least the kind that box people into a corner. The only techniques I like are the ones that make things clear and help people come to a fair decision. I’m very open.

Sometimes I’m talking to the leader of a billion-dollar product manufacturer. Other times I’m talking to someone thinking carefully about their own personal brand. The stakes are different, of course, but they’re experiencing the same human moment. They’re hesitating. If that happens, I’ll sometimes say something like this:

“You don’t want to do this until you’re ready. That makes sense. But there are a few things you should know.

“I’m really good at what I do. Differentiation is my craft. And the fact that you found me at all is wild. There are eight billion people on the planet. That you found me, decided I might be able to help, and reached out defies the mathematical odds.

“You might be thinking, ‘I can always do this later. There might be a better time.’ Maybe. But just because I’m here now doesn’t mean I’ll always be here. I might have a stroke. I might have an accident. I might decide to leave this field and do something else. I might decide to quadruple my fees.

“You just don’t know.

“What you do know is that I’ve already demonstrated I can help you in a meaningful way. You’ve said that yourself. And just because the opportunity exists now doesn’t mean it will exist later. If you walk, that’s not a neutral choice. It’s a gamble.”

I didn’t learn the existential close in any sales manual. I’m not trying to scare anyone. I’m not talking about their mortality. I put it all on me. I’m just naming something true about the human condition: things change, people disappear, and windows close.

Whatever they decide, I’m at peace with it. I told the truth.