The Box That Didn't Care What I Thought

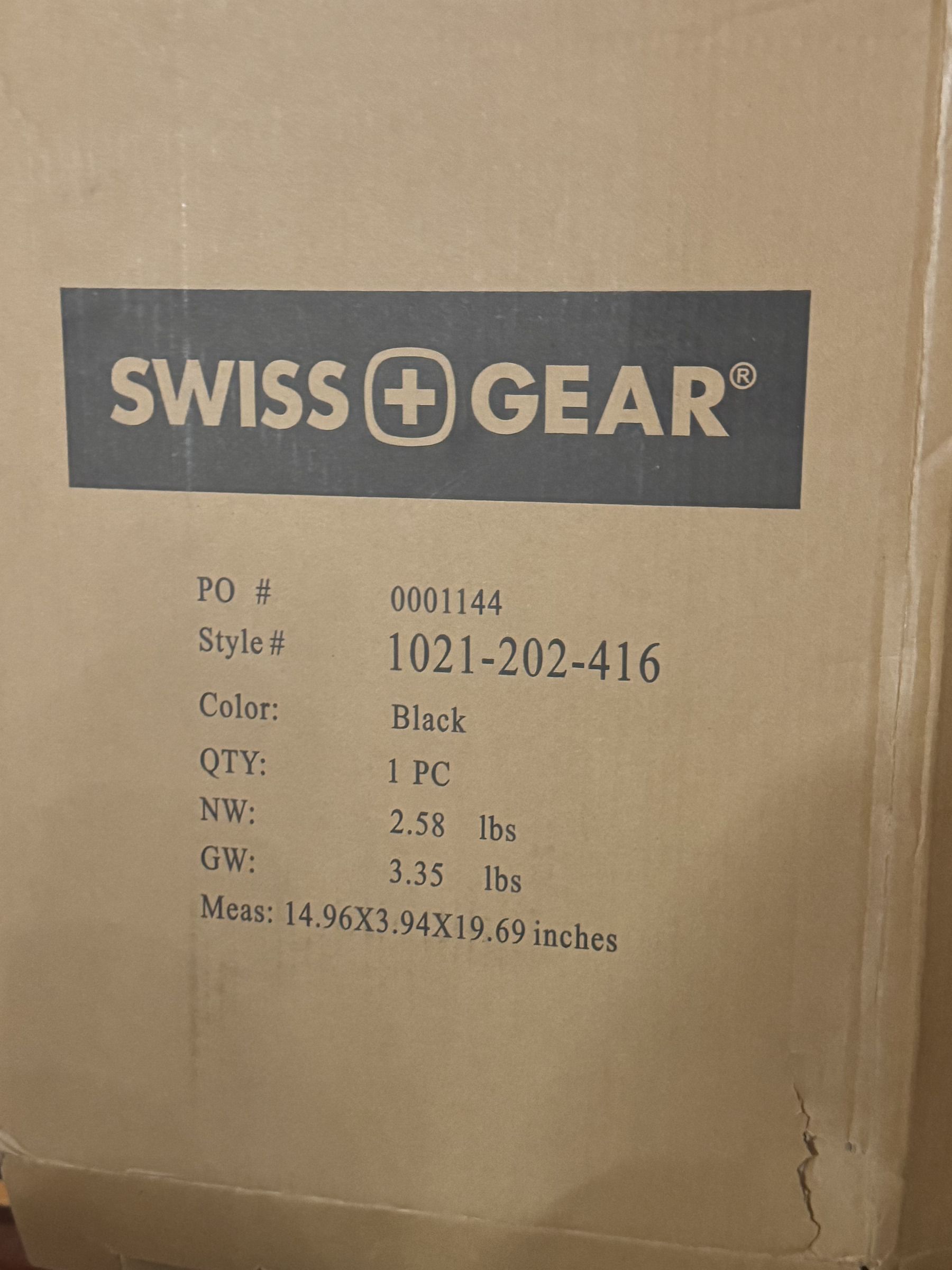

For Christmas, my wife bought me a SwissGear backpack. Before I even took the backpack out, its box caught my attention. Not because it was attractive or clever, but because it was aggressively uninterested in me.

Printed on one side of the box were the familiar details of logistics: PO number. Ten-digit style number. Quantity. Net weight. Gross weight. Measurements to the second decimal place. It was inventory and warehouse language, pure and simple. I could almost hear the beep-beep-beep of a tractor-trailer backing up to a loading dock, ready to off-load skids.

But then I turned the box over and found a subtle, yet profound, variation. While most of the information was identical – the PO number, the style, the color – the weight details were replaced with something else: “Carton # ___ of ____.”

This wasn’t just a blank space. The second number, 290, was printed, a clear indicator of a vast shipment. But the first number, 38, was handwritten in black marker. A distinctly human touch on an otherwise sterile container.

This small detail amplified the box’s core message. The box wasn’t telling a story; it was refusing to tell one. The handwritten “38” wasn’t for me, the end consumer. It was a mark of process, a note from one part of the system to another. It conveyed an even greater, more fascinating indifference. It was as if a worker on the line noticed something, made a mark, but the line never stopped moving. The system acknowledged a human was there, but only as another functional part of the machine.

The message the box conveyed was blunt: this is one unit in a system. This is carton 38 out of 290. The system does not care whether you’re paying attention. It will work anyway.

If you take that posture seriously, it starts to imply something more specific. SwissGear isn’t saying, “Look how carefully this was made.” They’re saying, “Here is one unit moving through a machine designed to handle millions of units without drama.”

And oddly, that restraint—that raw, unadorned display of process—creates confidence.

Which raises a harder question. If someone stripped away your company’s language and left only the system underneath, would it hold up? Or are words doing more of the work than the machinery beneath them ever could?