For Kenneth "Shark" Kinney

On September 13, 2025, the speaking community lost a beloved colleague and friend. This is the script I delivered during an online memorial organized by the National Speakers Association, honoring Kenneth “Shark” Kinney, a speaker, communicator, husband, and father. I’m sharing it here as it was spoken, in gratitude for having known him and in remembrance of the life he lived so fully.

I first met Shark three and a half years ago, the way many of us meet in this business — while waiting in front of a hotel for an airport ride after a conference. It happened to be an NSA conference.

Shark invited me to share his Uber. And on that short trip to the airport I learned that his nickname wasn’t just marketing flash. He actually loved sharks. He studied them. He swam with them in open waters. And, while championship golfer Greg Norman is famously known as “The Shark,” because Norman is a killer, Kenneth was “Shark” because he loved the sea creature. He loved sharks. When he was telling me about the habits of hammerheads and great whites, it was like he was telling me about his best friends.

A couple of years ago, Shark told me he was launching his own conference. It was for the home services industry. I asked him, “Why would you do that?”, and he said he was tired of waiting to be picked to speak. He wanted to do the picking. So he created his own stage. And true to form, that first conference wasn’t in a boring hotel ballroom. It was at a major aquarium, with tanks surrounding the room — and there was even a gigantic 55 foot whale shark drifting past the speakers as they spoke.

And Shark was always about the other person. So even though it was his conference, he shined the spotlight on others. He brought me in to speak, and he brought in Mandy Harvey, Susan Frew, and Fotini Iconomopoulos. He always made us the stars.

The last time Shark and I spoke was about three weeks ago, right when Cracker Barrel had changed its logo. I told him I hadn’t been to a Cracker Barrel in over a decade, and he said while he didn’t go often, but he happened to go to one a few weeks earlier. And the shocking thing he said was that now they served beer and wine. I said, “Cracker Barrel? They’re THE family restaurant. There’s no way they serve beer and wine.”

So he texted me a 24-second video he took of the drink menu. Then he laughed, saying: “I don’t know why I made a video of the menu. I should have just taken a photo.” (The things you remember, right?)

We hung up, I watched the 24-second video, and texted him back a funny comment about the restaurant. And the very last words he ever sent me were “Haha.” And somehow that feels right. Those are good last words.

Shark was an excellent guy. I feel lucky to have known him. And I’ll always remember him as a shark . . . in the best possible sense of the word.

"I'm a Karloff Guy"

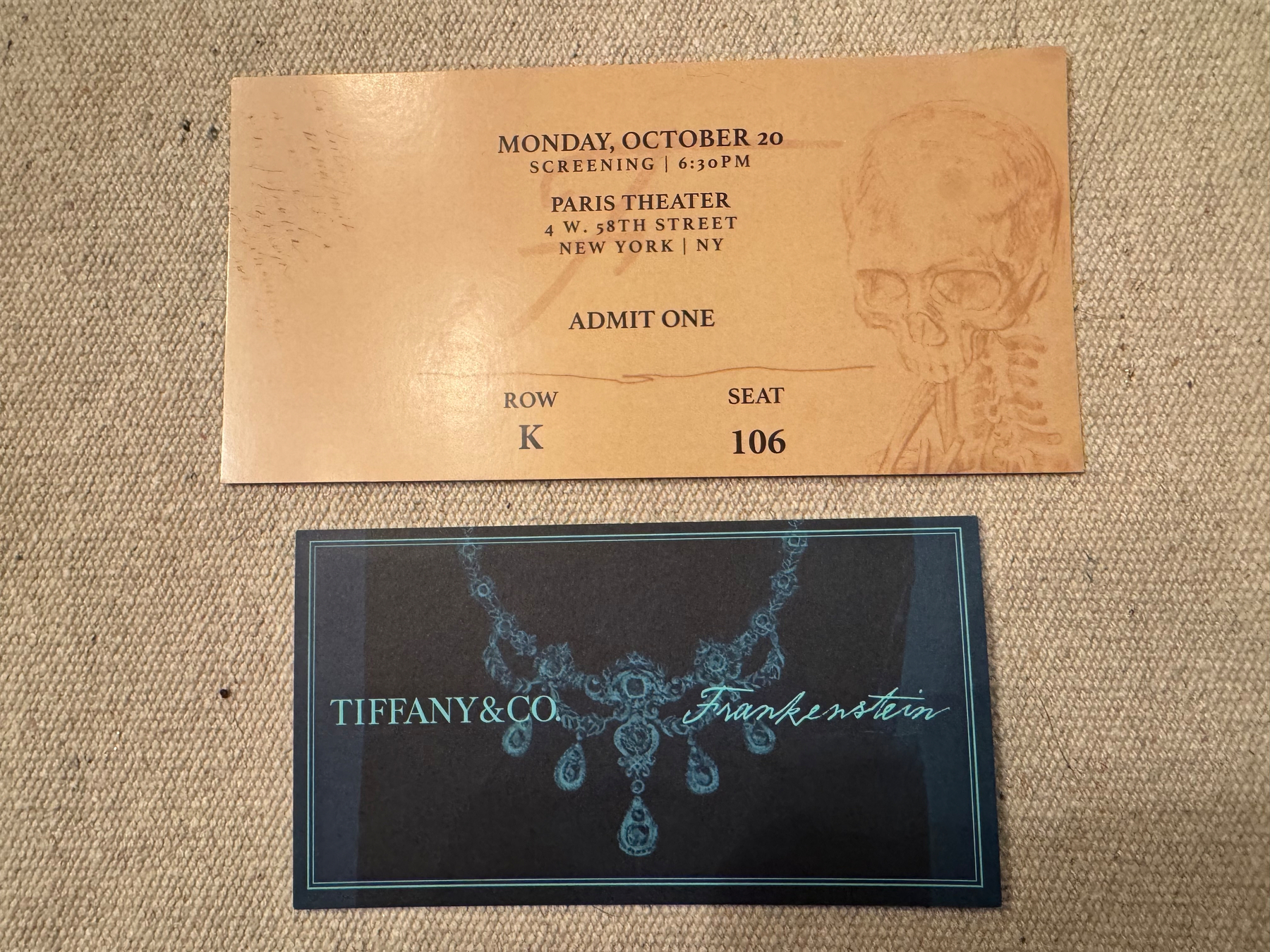

Several months ago, on October 20th, 2025, I had the pleasure of attending a screening of Guillermo del Toro’s new film, “Frankenstein,” at the Paris Theater in New York City. Guillermo is a supporter of “Chamber Magic,” the magic show I co-created with Steve Cohen, and even wrote the foreword to our coffee table history of the show. He had invited Steve, who in turn brought me. From start to finish, the evening was surreal.

After the film, at a party at Tiffany’s, I spotted Oscar Isaac. He had just played the scientist Victor Frankenstein in the very movie we had all just watched. Of course, Isaac is also famous for playing Poe Dameron in three “Star Wars” films – the man has his own action figure! – but I’m a huge admirer of his work in the Coen Brothers’ masterpiece, “Inside Llewyn Davis.”

The ending of that film is famously ambiguous. Seizing the moment, I asked Issac about it. He was a great sport, but argued for a rather pessimistic conclusion. Citing a couple of scenes from the film, I pushed back, arguing for a happier, more hopeful interpretation of Llewyn’s fate. For a few minutes, I found myself in the bizarre position of debating the meaning of “Inside Llewyn Davis” with Llewyn Davis himself.

Later that evening, I found a moment to speak with our host. “Guillermo,” I said, “today is October 20th. Do you know whose birthday is it?” Guillermo paused, a flicker of consideration in his eyes as he sorted through the vast library of his mind. Finally, he admitted he didn’t know.

“Bela Lugosi!” I announced. “And if Bela were alive today – and who knows, maybe he is – he would be 143.”

A smile spread across Guillermo’s face. “Ah, right! I actually knew that,” he said, “but I’m a Karloff guy.”

In a previous post, I wrote about the power of reduction: the way we’re often pigeonholed by others. But Guillermo’s declaration was different. Here he was labeling himself. Being a “Karloff guy” wasn’t a pigeonhole. It was his chosen identity; a shorthand for his passion. It’s the story he tells himself about who he is.

If you had to reduce the totality of your being down to one happy thing, what might it be?

The Explanation Was On the Side

I’m a differentiation expert. Over the years, I’ve helped create hundreds of brand stories. You might assume that would make me jaded. But it hasn’t. Every now and then, I still buy into a brand story for the romance of it.

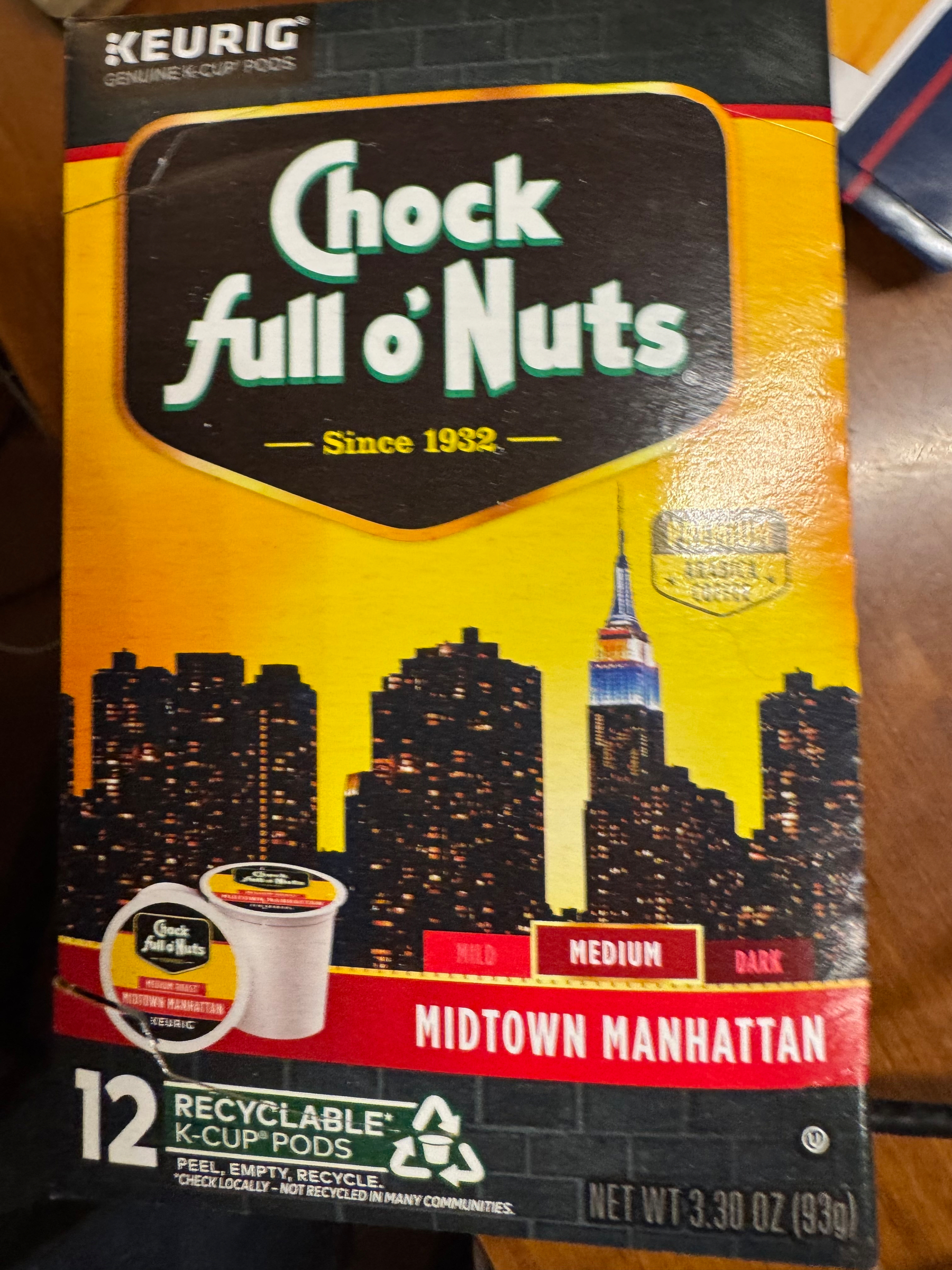

A few days ago, I was in the supermarket and noticed a box of coffee pods from Chock full O’Nuts. It’s an old brand, one I remember from way back. What stopped me, though, was the flavor name: Midtown Manhattan.

The front of the box showed a loosely sketched New York skyline. Most of the buildings were intentionally indistinct. One wasn’t. The Empire State Building was drawn clearly and in color.

I grew up in Queens, New York, but for the first thirty or so years of my life, Midtown Manhattan was where I spent most of my time. I took the 7 train in. I went to Tannen’s Magic at 1540 Broadway. I met friends, went to movies, had lunch, dinner, wandered. Midtown wasn’t something I mythologized. I mean, the streets were gritty and dangerous (Think: The French Connection, Taxi Driver, and Serpico). But the place was familiar.

I bought the box of coffee because I knew that every time I opened the kitchen cabinet and saw it, I’d smile. So I was buying a week and a half worth of smiles.

I brought it home and put it away. This morning, though, when I opened the cabinet, I noticed the box’s side panel for the first time.

At the top was a circle. Along the top and bottom edges of that circle it said PREMIUM COFFEE. In large letters inside the circle it read NO NUTS. Below that, written in the first person, was the company’s compressed history:

1920s: We sold nuts.

1930s: We sold nuts and coffee.

NOW: We don’t sell nuts. We just sell coffee.

But we like our name. CHOCK FULL O’ NUTS. PREMIUM COFFEE. NO NUTS.

INGREDIENTS: COFFEE.

I especially love that line, “But we like our name.”

For roughly the first fifty years of the company’s life, having “nuts” in the name wasn’t a problem. Nut allergies either weren’t as prevalent, weren’t recognized the way they are now, or were misrecognized. Over time, especially starting in the 1980s, that changed. Nut allergies became medically defined, socially visible, and operationally serious. At that point, a name like this, attached to a product that didn’t contain a single nut, stopped being quirky and started being a liability.

What’s interesting is how the brand handled it. They didn’t rename themselves or bury the issue. They put the explanation on one side panel, made sure you couldn’t miss it if you were looking, and then didn’t let it interfere with anything else.

What I admire here is the deliberateness. They told the truth once, in plain language, and trusted the customer to absorb it without being managed.

In business, differentiation is often framed as a lot of newness, as in a lot of invention, new positioning, new claims, new language. But it can be knowing exactly where to put the explanation so it’s available but not intrusive, and then having the confidence to say this is who we are and we’re fine with it.

What's Your Vision Really Made of?

A while back, I wrote a post called “What’s Your Parlor Trick?” The idea was simple: every professional should have a five-minute demonstration of their skill that makes an important stranger say, “Oh, wow. Now I get it.” It’s the magician’s answer to the request, “Let’s see a trick.” It’s an outward-facing demo that proves your capability to others.

But what happens when the person you need to convince is yourself?

This is a different, and often harder, challenge. When we’re developing a new idea – a new business, a new project, a new strategy – we are our own first audience. And we are notoriously easy to fool. We can talk ourselves into believing a vague vision is a brilliant one.

People often come to me with an idea and ask if it would make a good book or a TED Talk. My answer is always the same: “I don’t know. Write it. Let’s see what the writing says.”

Sometimes you don’t know until you’ve tried the thing itself. Until you’ve prototyped. This is where we need to move from a demonstration of skill to a manifestation of the idea. In these moments, telling isn’t enough. We need to show. But this time, the trick is for us.

A couple of decades ago, I read the designer and leadership expert Keith Yamashita refer to a concept that perfectly captures this. He called it a “vision deliverable.” The idea is to stop talking and start making. Says Yamashita:

“Force yourself to produce ‘vision deliverables.’ To see holes in your vision, write it down. First articulations are difficult, but they’re painfully necessary. Force yourself to pen a brochure, or a script, or a major speech, or do anything that forces you to recount your vision to the outside world. You’ll immediately recognize its vulnerabilities. Then rework your vision so it can withstand the slings and arrows.“

This isn’t a parlor trick to impress a client. It’s a vision prototype; an internal tool for discovery. In fact, asking a client to prototype their fledgling idea in some form is a common homework exercise of mine. As Yamashita implies, you don’t wait until it’s bulletproof. You create the prototype precisely to find the holes. You show it to yourself and others to see what works and what needs to be fixed.

These prototypes can take many forms. For example:

• A city library that wants to become a hub for digital skill-building could create the course catalog for the first quarter, listing the specific classes and times.

• A healthcare system that wants to provide a truly patient-centric experience could write a “journey script” for a single patient, detailing every ideal interaction.

• A financial firm that wants to be the trusted source of advice for Gen Z could script a 60-second TikTok video explaining a complex topic simply and engagingly.

• A national park that aims to drastically reduce its environmental impact could design the new park map showing the routes for electric shuttles and new low-impact zones.

• A company that wants to be known for its legendary, proactive customer support could write an entry in the internal support playbook, detailing the exact steps an agent takes when a problem is detected before the customer calls.

This trick – the prototype, the mock-up, the first draft – is what you do for yourself. It’s how you find out what your vision is really made of.

Subservient to the Work

When you’re a high-level advisor doing significant work, what’s the most important thing to focus on? Most people say the client. That seems obvious. It would be crazy not to put the client first, right?

But what if that’s wrong? What if the key to great work isn’t focusing on the client, or on yourself and how you’ll be perceived, but on the thing that needs to be created?

Ted Kooser, who was Poet Laureate of the United States, wrote about this approach to doing good work. He said that if poets focus on the romance of being a poet, they take their eye off the ball. If they focus on their own identity and gains, their work will suffer. Instead, he said, a poet must “serve each poem we write. We make ourselves subservient to our poetry.”

The work is the master. Our job is to serve it.

An approach like this requires that we set aside our ego. (Why?)

Because when you’re focused on ego – on acceptance, fame, or self-aggrandizement – your attention is split. You’re trying to solve the problem and manage how you’re perceived, which creates interference. Worse, it makes you conservative. You play it safe to avoid looking foolish, protecting yourself instead of serving the work.

When you shelve all that, you become free to see what the work actually requires, not what will make you look good. As the therapist Dr. David Reynolds told me, “You can’t work well while hoping that others praise your work, or that your work will make you rich. Progress comes when you shelve your emotions and demands for a while.”

I’ve had to use this principle when the stakes felt impossibly high. When advising people like the head of a division who served in two former White House administrations, or the former president of UPS, you realize the work can affect millions of people and countless amounts of money. The natural reaction is, “Gulp! What do I do?”

But I never think like that. Why? Because I’m focusing on the outcome as something beautiful and separate from me and my client – like an object floating in Plato’s theory of forms. I’m just trying to make that thing as bewitching as possible. That focus dissolves the pressure.

When you focus on the work itself, ego and personality fall away. You don’t worry about who gets the credit or whether you look smart. You are both simply servants to the highest version of what needs to be created.

The Differentiation Brag Sheet

Most people like the company they work for. Many are even proud of it. But far fewer can talk about the company in a way that sounds specific and credible when there’s no slide deck or formal pitch involved.

Ask someone casually what their company does well and you’ll often hear generalities. “We really care.” “We do great work.” “Our people are amazing.” None of that’s false. It’s just not very persuasive.

That’s the problem a Differentiation Brag Sheet is designed to solve.

A brag sheet is an internal document, usually one to three pages long, that gives everyone in the organization a shared set of facts and stories they can draw from if they want to talk about the company. It is not a formal speech to memorize. Rather, it’s a collection of discrete pieces of information. Think “LEGO bricks,” not a single script. People don’t need to use all of it at once. They only need to know a few pieces well enough to use them naturally. Let me give you an example.

Picture yourself standing in line at Starbucks, or sitting at a neighborhood bar. Someone you’ve just met asks where you work. They don’t know your company well, but they’re curious. They may even be a potential client. At some point, they say, half-joking and half-serious, “So do you guys actually know what you’re doing?”

In that moment, the answer doesn’t need to be clever. It just needs to be concrete.

“You bet we do. I mean, we’ve been in business for 20 years. In 20 years we’ve completed almost 4,000 projects. We have 214 repeat clients, and our repeat clients hire us, on average, for 16 projects each. You don’t do that kind of long-term work without knowing what you’re doing.”

Those aren’t marketing claims. They’re evidence.

A strong brag sheet also includes a small number of stories that substantiate the position the company is claiming. Not hero stories. Just real incidents that show how the company behaves when something is at stake.

I worked on a Differentiation Brag Sheet for an industrial architecture firm whose founder believed the market viewed industrial architects as unreliable businesspeople. Creative, yes. But inclined to go over budget and miss deadlines. Fair or not, that perception existed, and it was hurting them.

So we built the brag sheet around a single idea: reliability. Every fact, number, and story had to reinforce that idea. Here’s one of the stories the founder told me.

Late one rainy Sunday night, around 10:30, his phone rang. The caller was a prospect, not a client. The man was almost in tears. He was scheduled to sell his current building the next morning at 9 a.m. That sale was going to fund the purchase of a larger, better building in a more desirable part of town later that same day. The timing, though, was unforgiving. If the morning sale was delayed, the funds wouldn’t be available in time, and other buyers would step in and purchase the new building.

As he reviewed the closing documents that night, he saw a problem with the sale of his building that he hadn’t noticed before. There was a blank space asking for the building’s height and width. He didn’t know them. And he had no idea how to get them on a rainy Sunday night.

Panicking, he called the industrial architect out of desperation. He figured an architect might know whether there was anything he could do, or whether the whole deal was about to collapse.

The architect listened and said, “Don’t worry. I’ll meet you tonight at your building, and bring an umbrella because it’s pouring.” They met at the building, went up to the roof, and the architect brought a laser measuring device. In the rain, just after midnight, he measured the height and width of the building and carefully wrote the numbers into the closing documents by hand. The next morning, the sale went through without a hitch. The purchase happened that afternoon. The prospect became a client.

That story earned its place on the brag sheet because it made the firm’s position undeniable. Reliability wasn’t a slogan. It was a behavior demonstrated for someone who hadn’t even hired them yet.

That’s the real purpose of a Differentiation Brag Sheet. Decide what you want your company to stand for. Gather the facts, figures, and stories that support that idea. Write them down. Share them internally. Let people use them when it’s useful. Over time, your company will start to sound like it knows exactly who it is, because it does.

I learned this approach to strategic messaging from people like Jaynie Smith, along with others who focus on helping organizations align what they say with what they actually do.

The World's Greatest Consultant

In my keynotes or when I lead working sessions with groups of leaders, I’ll often shift gears and say, “I now want us to do an exercise I call ‘The World’s Greatest Consultant.’ And who is the world’s greatest consultant? It’s you. Each one of you has the know-how, the perspective, and the brilliant listening abilities to help turn a stuck business problem around. You have invaluable advice to offer.”

Then the work starts, and the room comes alive.

The exercise itself is a powerful twist on the “Blurt It Out” method from Chris Baréz-Brown’s book, How to Have Kick-Ass Ideas. It’s a way to generate incredible ideas, and it’s a tool you can immediately bring back to your own team.

How to Run the Exercise

I have everyone pair up, designating one person as Person A and the other as Person B. I make it clear that they’ll both get a turn in each role before giving the specific instructions.

Round #1. The Seven-Minute Download: “Person A, you’re first. You’ve got a real business problem, one that’s keeping you up at night. I’m going to keep the time. For the next seven minutes, I want you to download everything about it to Person B. And I mean everything. Don’t worry about logic or making sense. Just talk. Do it fast and don’t stop talking for any reason whatsoever. Tell the stories, the failed attempts, the frustrations, the crazy ideas you haven’t told anyone.

“Your partner, Person B, is now the World’s Greatest Consultant. Their only job is to listen and jot down anything that seems important, interesting, or just plain weird.”

Round #2. The Three-Minute Consultation: “Time’s up. Now, Person B, you’re on. You have three minutes to be that World’s Greatest Consultant. Tell Person A what you heard. Again, do it fast and don’t hesitate for even a second. What stood out? What patterns did you see? Don’t be shy – throw in your own ideas and opinions. You’re the fresh pair of eyes. Person A, your job is to just listen and take notes on what lands with you.”

Round #3. The Two-Minute Debrief: “Alright, Person A, you’re back up for the final two minutes of the round. This is crucial. Don’t leave the World’s Greatest Consultant hanging. Tell your partner what you heard from them that was most useful. What are you thinking now? They just gave you their undivided attention and brainpower. Let them know what struck you as something to contemplate or maybe even use.”

Once this initial 12-minute timed exercise is over, and I have them switch roles and run it again. Now, Person B picks a troublesome problem, and Person A serves as the World’s Greatest Consultant.

So, Why Does This Work So Well?

This exercise isn’t just a gimmick; it’s based on solid principles. The seven-minute “download” is basically a freewriting conversation. By forcing you to talk fast and continuously and without a filter, it helps you bypass your internal editor – that nagging voice that shuts down ideas before they’re fully formed. You get the raw, unfiltered truth of the problem out on the table.

Then, your partner comes in as a completely fresh set of eyes. They aren’t bogged down by the history or the emotional baggage of your problem. They can spot connections and opportunities you’re too close to see. The tight time limits are also key; they create urgency and focus, preventing the conversation from fizzling out into a generic chat.

A Quick Word on Pairing People

If you’re running this with a group, be a little strategic. You probably don’t want to pair direct competitors or an employee with their direct boss; that can get dicey. The best results often come when you pair people from different departments or even different industries. The fresher the perspective, the better.

So, the next time your team needs a jolt of creative energy, give it a shot. Don’t just read this. Try it. The result, I think, might astonish you – and I say this from experience.

Why a CEO Would Buy a Book in Bulk

Years ago, I asked my friend Steve Piersanti a question that had been bothering me.

Steve is the founder of Berrett-Koehler Books, the publisher of my book Accidental Genius, and someone who has seen more books succeed and fail than almost anyone I know.

I asked him, “What actually causes a CEO to buy books in bulk? You know, not buying five copies, but buying five hundred or even five thousand copies.”

I thought Steve would think things over. Instead, his answer was immediate. He said CEOs buy books in bulk for two reasons.

The first reason goes like this. A CEO reads a book and says to their leadership team, “You see this book? The expert who wrote this book says great organizations should be doing exactly what we’re doing here already. So you see, I told you this was the right way to go. I’ve been right all along.” Then they buy a copy for everyone in the company, so everyone can see that they were, in fact, right.

The second reason is a variation on the same theme, just with more bite. A CEO reads a book and says to their leadership team, “You see this book? The expert who wrote this book says great organizations should be doing exactly what I said we should be doing – only we haven’t been doing it. Why? You fought me on it. You questioned me. You slowed us down.” Then they buy a copy for everyone so the message lands with extra authority. “Maybe you’ll listen to me next time.”

What they don’t do is buy a book in bulk and say, “Look how wrong I’ve been. Please enjoy this detailed explanation of my mistakes.” People don’t buy books in bulk to confess error.

They buy them to immortalize agreement. It’s agreement between them and the expert.

Which leads to a useful, slightly uncomfortable insight for anyone writing a book. Your job is not to convert people who fundamentally disagree with you. That’s not how books move at scale. Books move when they give readers language and reinforcement for what they already believe to be true. You’re not writing for skeptics. You’re writing for allies, and for the people who read your book and say, “Yes, this is exactly what I’ve been trying to say.”

Now here’s the thing. This isn’t only about books. This is how ideas spread, products get adopted, and movements gain momentum. People don’t amplify things that make them look wrong. They amplify things that make them look right.

When does a leader share an article with their team? When it validates a decision they already made. When does a VP champion a new methodology? When it confirms the direction they’ve been pushing. When does someone evangelize a product? When using it makes them look smart.

The CEO buying books in bulk isn’t an edge case. It’s just how things work. We share things that make us feel understood. We pass along ideas that say, “Yes, that’s what I’ve been trying to say.”

So if you’re writing a book, launching a product, or trying to spread an idea, don’t aim at the people who don’t get it. Write for the ones who already do, and will recognize themselves on the page.

If You're Selling Air, Build a House

You’ve probably heard the idea that what feels obvious to you can be revelatory to someone else. That happened to me twice this week, with the exact same piece of information. Both times, I was working with a consultant on how to make their know-how shine. And both times, I found myself saying this:

“There’s an old advertising adage. The more concrete the thing you’re selling, the more ephemeral the advertising can be. The more ephemeral the thing you’re selling, the more concrete the advertising needs to be.

“What’s that mean?

“If you’re selling a tangible product, say a car, and you advertise that it has 500 horsepower, but I’m selling a car with 600 horsepower, I win. That’s one reason car advertising so often avoids specifics and instead leans into qualities, moods, and feelings. Things that are hard to measure, and therefore harder to out-compare.

“But if you’re selling something ephemeral, like advice, strategy, or insight, people want the opposite. They want to know what they’re actually buying.

“They want to know how many years you’ve been doing this. Who you’ve worked with. How many clients come back. What you believe. What frameworks you use. How you think.

“In other words, they want proof that you’re not just some person with opinions.”

So you have to do something slightly counterintuitive. You have to conceptually build a house for them. Good floor plan. Solid walls. A sense of structure they can walk around in. Only then can something intangible start to feel real. Only then do they realize that there’s a “there” there.

Why They Told Their Friends

This is the opening of a keynote I gave a few years ago to an audience of founders and CEOs.

It’s about differentiation and how to create evangelists. More precisely, it’s about how to get people to talk about your business, your product, or your service, without twisting their arm.

I focused on one tool that makes all of that possible. That tool is story. Not story as branding, and not story as mythology, but story as something people remember and repeat. Something that travels easily from one person to another.

I know a lot about how to get people talking about businesses and products and services, and much of what I know comes from my background as a magician.

I’ve been a magician since I was four years old, and I co-created Chamber Magic, a live show that has run for well over two decades and was, for a long time, the number-one ranked live show in New York City on TripAdvisor. Over the years, our audiences have included people like Warren Buffett, Stephen Sondheim, Guillermo del Toro, and Shaquille O’Neal.

When the show began, we had no money. None. Everything had to be done on the cheap, which meant we couldn’t rely on advertising or publicity to make the show famous. If the show was going to spread, it would have to spread because people talked about it.

So Steve Cohen, “The Millionaires’ Magician,” and I used a very simple procedure.

Steve would perform the show, and afterward I would walk up to people and say, “I’m with the show. What trick did you like best?” Then I would listen. I did this for months. The tricks people talked about stayed in the show, and the tricks they didn’t talk about were removed.

It was Darwinian; pure survival of the fittest. Because we didn’t have money, the tricks had to do the heavy lifting. They had to act as the show’s emissaries, even its missionaries. I knew something very specific: if people told me about a trick, they would tell their friends. And if they didn’t tell me, they wouldn’t tell anyone.

Over time, I became very knowledgeable about how to make a trick that people would talk about, and it turns out that what makes a trick talkable is almost exactly what makes a business talkable too.

Here’s the first lesson. A trick can’t be subtle.

Suppose I ask you to lend me a coin. The date on the coin reads 2020. I wave my hand mysteriously over it, and now the date reads 2021. Is that a good trick or a bad trick? It’s a bad trick, and the reason is simple. It’s too subtle.

You might think, “Maybe I misread the date. The lighting isn’t great. Maybe it said 2021 the whole time.” In other words, the trick gives your mind too many exits.

If you want to truly freak people out, the thing you do has to be bold. Instead of changing the date on the coin, it would be far better if I changed the coin into a live box turtle. And better still, if I borrowed your coin, had you sign it with a Sharpie so we could identify it, and then transformed it into a turtle with your autograph written across the shell.

That is a story you would remember and would be excited to tell. And that is a story that would move from you to someone else without any resistance.

Here’s the second lesson. The premise of a trick has to be clear. It can’t be confusing. As the great twentieth-century magician Dai Vernon once said, “Confusion is not magic.” If the audience is confused about what happened, that confusion stands between them and astonishment. They may be fooled, but they won’t be astonished.

And people don’t talk about things that fail to astonish them.

If all of this sounds like it only applies to magic, it doesn’t. It applies to businesses too, including businesses like yours.

In the keynote, when I delivered that last idea, I didn’t follow it up with advice. I didn’t show a framework or a slide. I let the founders and the CEOs in the audience do their own work. Because once you see the difference between a coin quietly changing its date and a signed coin turning into a live turtle, you don’t really need to be told what to do next.

What Makes You Essential? An Insight

I’ve read a lot of case studies. Most of them are fine. They follow the usual script: here was the problem, here’s what we did, and here’s the great result. But they almost always leave out the most interesting part.

They miss the moment someone saw something that everyone else had overlooked. That little spark of insight that made the whole solution possible.

I call it an Insight-Based Case Study. It’s like getting an x-ray of the consultant’s mind. You see how they think, not just what they did. It’s the difference between a checklist and a breakthrough. And it’s how you know that particular person was essential. Without them, that groovy insight might never have happened.

Here’s a quick, fictional example of what I mean, broken down.

The Problem They Had: A software company was losing customers. People would sign up for a free trial, poke around, and then disappear. The leadership team was convinced they were in a feature war and needed to build more stuff.

They Hire a Consultant: A consultant comes in. Instead of just looking at the competition, she starts by talking to people—the customers who left and the ones who stayed. She digs into the data to see what people were actually doing.

What She Saw That No One Else Did (aka The Insight!): She noticed something interesting. People weren’t leaving because the product was missing features. They were leaving because they were overwhelmed. They never got to that first small win that makes you love a product. The problem wasn’t a feature gap; it was an onboarding gap.

What They Did Because of Her Insight: Because of this, she convinced them to stop building new things and focus all their energy on fixing the first 15 minutes of the user experience. They created a simple, guided path to help new users get that first win.

The Result They Got: The change was huge. More people started converting to paid accounts, and fewer customers left. All because someone looked at the problem a little differently.

When you tell a story this way, you’re not just sharing a win. You’re showing how you think. And in the end, that’s what people are really buying.

16,000 Years

I was in my early twenties and had to take a cross-country plane flight. The trouble was, it had been a dozen years since I’d been on a plane, and I’d developed a case of nerves. So I read a book about it.

In the book I found a few things that stuck with me. At the time, it said that to die in a plane crash, you’d have to take two flights a day for 16,000 years. OK, good odds! It also compared a plane in turbulence to a motorboat going over waves; you want the boat to go up and down and move with the water. That’s what keeps it safe. Same with a plane.

The book also suggested visiting the cockpit before taking off. This was pre-9/11, so I asked a stewardess if I could. She showed me in. The pilot asked, “Did you want to learn how to fly, so you can be a pilot?” “No,” I said, “I’m just interested in what’s what.” He showed me the controls and the printout of the weather pattern, so we could fly above it at the right moment. I ended up loving to fly.

I still approach fears the same way. A couple of years ago, I needed cataract surgery. They use a machine to get your exact prescription, then they have these soft lenses custom-made to match it. They cut a circle in the lens cap in the front of your eye, lift the flap, suck out your biological lens with a little vacuum, throw it away, and take your synthetic lens all folded up and let it open up on your eye. Then they close your eye back up. In a very real way, it’s like they seared your eyeglasses into your head permanently.

By the time my eye surgery day came, I was pretty relaxed. In fact, while I was waiting in the prep room beforehand, the other patients on their gurneys were answering the nurses’s questions in nervous monosyllables. Yes. No. Me? I was gabbing with a nurse about birdhouses and what the best seed was to attract cardinals.

It’s not that I’m particularly brave or smart. And I don’t want to know every scary detail. I just have this rule for myself: I want to know about what I fear in enough detail that I can entertain my friends with it. If I have that, I’m good.

How to Add Something to the World

If you’re trying to write a post, a book, or create IP of any kind, it helps to remember this: your idea does not have to rattle the world. It only has to add something to it. A small contribution is still a contribution.

Often, the work of creating something “original,” or at least useful, is simply noticing the ordinary, or moving an existing idea from one context into another.

Years ago, I took a stand-up comedy class, and the teacher, Stephen Rosenfeld, said something in passing. He told us that jokes come from “walking around in truth.” He didn’t linger on his comment, and he certainly didn’t present it as a grand theory. It may have been a throwaway line. For me, though, it was an instruction I could actually follow.

I started moving through the day a hair differently, as if I were a Martian whose job was to observe human life and report back. I paid attention to imbalances and absurdities, and to things everyone sees but few bother to remark on.

One afternoon in Walmart, I noticed a merchandise table holding three stacks of folded T-shirts. From a distance, the left stack and the right stack were equally tall. The middle stack, though, was far shorter, maybe a third the size of the others. I walked over.

The left pile consisted of smalls and extra smalls. The right pile consisted of larges and extra larges. The short center pile was exactly what I expected, all mediums. The joke followed naturally. Why do they make extra smalls and extra larges, but not extra mediums?

Another day, in a supermarket, I stood in front of a skid of bottled water. Then I thought about the fact that human beings are mostly water, roughly sixty percent. The joke became, if sixty percent of a human being is water, then drinking Poland Spring is cannibalism.

I didn’t invent anything. I just looked past the assumptions about what I was seeing and how I was supposed to interpret it.

The same habit shaped a magic effect I created for Steve Cohen, “The Millionaires’ Magician.” He was meeting a New York Times reporter in Central Park, and they walked toward the river. Steve asked the reporter to think of a place he had always wanted to visit but hadn’t, and to hold that place clearly in his mind.

Then Steve asked the reporter to take a coin from his pocket. He handed the reporter a black Sharpie and asked him to mark the coin. Steve had the reporter kiss the coin, make a wish that he someday visit the place he was thinking of, and throw the coin as far as he could into the river.

Only after the coin was gone did Steve begin “reading the reporter’s mind.” “I see trees,” Steve said. “Rocky terrain. You’re walking uphill, on a long trail. You’re thinking of the Appalachian Trail.” That was the place! An apparent miracle.

Steve smiled, as if this solved something. “That’s your lucky coin now,” he said. “Let’s get it back for you.”

Steve rolled up his right sleeve, closed his hand into a fist, and water began magically seeping out between his fingers. When he opened his hand, the reporter’s signed coin sat in his palm.

That effect came from things I already loved, and simply placed side by side. As a kid, I thought wishing wells were small miracles tucked into everyday life. I also loved an old magic trick where playing cards are thrown away repeatedly, yet somehow keep returning.

So I treated the river as a wishing well, and I let the coin behave like the cards in that old trick. Nothing new, exactly, but newly arranged.

Out-of-Character Advice

I once had a conversation with Dr. David K. Reynolds that I remember to this day, because the advice he shared seemed so out of character for him. David created Constructive Living, a therapy rooted in lifelong, disciplined work. His action-oriented approach, drawn from Zen and Morita Therapy, is about acting on your purpose despite your feelings – over and over and over and over again. He’s vehemently against quick-fix solutions.

But, as you can imagine, such long-term disciplined action is a scary proposition for a first-time patient who just wants instant relief. David knows this, and he’s a pragmatist.

“In that first session,” he said, “if I don’t give them something that helps them quickly, they’ll never come back for a second session.”

So what does David give them? A special homework assignment. And that assignment is as follows: “Go home and clean your apartment or house.”

David isn’t speaking in metaphors; this is a literal prescription.

Assuming there is no medical issue at play, the house-cleaning task immediately redirects their attention from their internal turmoil to a useful external goal. It gets them out of their head and into the physical world. And it allows them to accomplish something tangible that contributes to their own daily maintenance. When they finish, something in their life is objectively, undeniably better.

Naturally, this single act doesn’t provide a cure. But it’s a concrete win that provides just enough relief to create hope. And hope is what brings them back to David’s office for the disciplined work that lies ahead.

Whether or not you believe in this particular therapeutic approach isn’t the point. Instead, what I want you to think about is this: If you’re leading a team or working with clients on complex business problems, remember that you need to help them with their pain sooner rather than later.

We often hear that you shouldn’t just solve a symptom and think you’ve solved the problem. That’s true. But sometimes, helping with a symptom is what keeps people in the saddle long enough to solve the bigger issue.

Editing Out the Lies

A number of years ago, I had a client who was a leadership consultant. He asked me to read over a blog post he had written, so I could tell him what I thought. I read it, and at a key moment, he had written, “Great leaders always learn from their mistakes.”

Immediately, I knew what I was reading wasn’t real. It sounded phony. It sounded like what Tolstoy would call “head-spun," as in, it came from the mind, not from lived experience.

So I told my client, “Look, I know a lot of great leaders — of major organizations, in the military, in government, and so forth — and I can virtually guarantee you that none of them always learn from their mistakes.

“Now here’s the thing: that phrase sounds dramatic, and it sounds like it should be true. But if you write it, people trust you, and now you’re setting them up with unreal expectations. They won’t learn from a particular mistake, and they’ll blame themselves. But really, you screwed them up. They just believed your lie.”

The next day, he sent me four other posts with a message: “Mark, I wrote these before speaking with you yesterday, so I went back over them and edited out all the lies. Can you look them over and see if I missed any?”

You don’t want to lie in your writing. You want to tell the truth, at least as you understand it. This is why I love the following quote from Robert Newton Peck:

“The basis for my success is that I write about what people do. Not what they ought to do.”

More than a hundred years earlier, Henry David Thoreau wrote something similar:

“Say what you have to say, not what you ought. Any truth is better than make-believe. Tom Hyde, the tinker, standing on the gallows, was asked if he had anything to say. ‘Tell the tailors,’ said he, ‘to remember to make a knot in their thread before they take the first stitch.’ His companion’s prayer is forgotten.”

Truth is preferable because it connects with reality and, therefore, with the reader. When you write what is true — based on real, lived experience — your words will land.

Risking Sentimentality

I was digging through a computer folder and found a transcript from a keynote I gave about a decade ago. It’s a story I used to tell about my two old Jeeps.

——-

In the past two decades, I’ve owned only two cars. Both were Jeeps, and I drove each of them for over 200,000 miles.

What gives? Am I just a creature of habit? Am I cheap? Do I have a passion for towing things? No, it’s nothing that practical. The reason I’ve only owned Jeeps and drove them that far is because of the story they represent.

It started when I was five. I’d break all my toys, but I had this one metal-and-hard-plastic toy — a small Jeep — that was simply indestructible. I could throw it, step on it, bury it in the sandbox, and it would not break. That made an impression on me.

Then, when I got a little older, my heroes were soldiers, and every soldier I saw on TV drove a Jeep. On the show “Rat Patrol,” the soldiers chased Rommel across North African sand dunes in a Jeep. In the movie “Patton,” George C. Scott commanded the Third Army from the back of a Jeep in the middle of a battlefield.

To me, these were hero cars. They were brave, tough, indestructible.

So when I grew up, what car was I going to buy? A Corolla? I never saw any Corollas chasing Rommel. A Chevy Impala? I don’t remember Patton leading his troops while standing in the back of an Impala. No, it was always going to be a Jeep.

And what was I going to do with my Jeep? I was going to drive it into the ground, because the story said you couldn’t run it into the ground. That was part of the fun. That was its legend.

This might all sound silly and emotional, but most of us make major purchases based on an irrational motive. A friend of mine drives a Lamborghini and loves to tell me it can go 220 miles an hour. Yet, he once got a traffic ticket for doing 40 in a 30-mile-an-hour zone. So what good is 220 miles an hour in a world that won’t let you do 40?

He didn’t buy his Lamborghini for practical reasons; he bought it for emotional ones.

Jeep’s story is that it’s the hero’s car. It’s legendary for being indestructible. So, my question to you is this: What is your business legendary for?

Is it a product, a service, an idea, or a quality? If you don’t know, you have clues. Look at your proudest moments. Look at what makes you different from everyone else. I guarantee you, the seed of your legend is there.

To talk about your business in a way that makes people care, you don’t just list features. You talk about what makes you proud, what makes you different, and most importantly, what makes you legendary.

——

Reading this now, that final question — “What is your business legendary for?” — feels corny. It’s the kind of thing a keynoter says, trying a little too hard to earn their fee by forcing in an oversized idea.

But then I think about something the late poet Richard Hugo wrote in his essay, “Writing Off Subject”:

“All art that has endured has a quality we call schmaltz or corn . . . if you are not risking sentimentality, you are not close to your inner self.”

And there it is. That’s the defense for the whole thing. In our rush to be cool and detached, we often run away from the very things that mean the most. We mistake irony for truth.

That “legendary” quality I was talking about isn’t an overblown marketing slogan; it’s the part of your work that you feel so strongly about, that you’re willing to sound a little corny when you talk about it.

Maybe that’s the real test. If you’re not risking a little schmaltz, you’re probably not talking about anything legendary at all.

Build a Database of What You Know

Most consultants I know dramatically underestimate how much valuable advice they have to share. They think they need a trademarked framework or a slick model with arrows pointing in reassuring directions. That’s a mistake.

It makes them overlook the far more valuable thing they already have: a whole library of ideas they routinely share with clients in conversation.

Forget the fancy frameworks for a minute. What you need first is a private database of what you know how to teach.

This isn’t a list of everything you teach every client. It’s a catalog of everything you could teach, depending on the moment. Think of it as a working archive where leverage quietly accumulates. You don’t consult from this database directly. You draw from it selectively, deliberately, and often invisibly.

Here’s the daily practice that builds it.

At the end of each day, write down two things you taught a client. Not what you delivered or produced. Write down what you explained. What you reframed. Or, the moment you helped them finally see something clearly. That’s when the real value changes hands.

Each entry in your informal database has two parts: the principle, then the story. Always list the principle first. The story comes second.

And by “story,” I mean the example you used to make your point. It could be the story of the client conversation itself – what you said, how it landed, and what the client decided to do with the idea. The story isn’t for entertainment. It’s for buy-in. People resist being told what’s true, but they relax when they recognize something familiar. A story lets them nod before they argue, and that nod is what makes the idea usable.

Here’s an example of what something I wrote down in my own database:

The principle: The first line of your elevator speech should be clear, not clever.

The story: I learned this elevator-speech approach from watching people listen. When you tell someone what you do, they’re trying to pigeonhole you as fast as they can so they can relax and know what’s expected of them. Your job is not to resist. By all means, let them put you in a conceptual box. It helps them loosen up and focus.

It’s like when you sit down in a restaurant and ask the waiter what’s good, and he starts rattling off exotic dish names you’ve never heard. You don’t relax into curiosity. You tighten up. You’re still searching for an organizing principle. But the moment you realize, “Oh, this is a Mexican restaurant,” everything shifts. Now you can actually hear what he’s saying.

Your elevator speech works the same way. Start with something blunt: “I help Apple and Intuit with their international growth.” The listener still doesn’t know how you do that, and that’s fine. If they’re interested, they’ll ask. If they don’t, no amount of cleverness would have changed that.

This is why I have a visceral reaction to cute elevator speeches like, “I’m a sherpa for executives.” It feels like the speaker is playing keep-away. The speech carries the odor of a sales pitch nobody asked for. When someone answers that way, I usually disengage. (Or, I say, “Friend, you need to hire me to help you, ASAP.")

This is what your database is really for. It’s not for publishing or branding, at least not at first. It’s for capturing the actual value you create in real conversations before it evaporates. That way, you can use your best ideas, insights, exercises, and stories, again and again.

A Harmless Mystery

I opened a ten-year-old document and found a draft of an email to a “Steve.” Through the years I’ve known dozens of Steves, including my dear friend Steve Cohen (“The Millionaires' Magician”), but I don’t recall who this Steve was.

Hi Steve,

I was watching a TV program and thought of you. Or, more accurately, I thought of the beautiful principle you champion: in business and in life, you should give to get, or give more than you could ever hope to get in return.

Apparently, the principle doesn’t work with humans only. I’ll explain.

The TV program was a BBC show, “Weird Wonders of the World,” and it profiled a girl from Seattle who had a bunch of clear, plastic carrying cases. Each case held dozens of small, bizarre curios: earrings, beads, metal nuts, screws, buttons, charms from necklaces, and so forth.

Why was she saving these odd things? Each was a gift from wild crows.

The girl put up feeders in her backyard, and she’d devotedly refill them with seeds and peanuts. When the crows swooped down she’d watch them and talk with them. She spent loving time with them.

After a while, these crows would reappear at the feeder with a trinket, which they’d drop near her before they’d eat. Over the years they’ve done this hundreds of times. (One returned the girl’s camera lens’ cover. Another gave her a crab claw.)

Crows apparently are one of the animal kingdom’s smartest creatures. They can use tools, and some tests show they’re smarter than dogs and cats.

The practice they are exhibiting is called “gifting.”

The young girl (at the time of the TV show she was 8; now I think she’s 13) gave to the birds without thought of remuneration, and they decided to repay her.

Anyway, I thought it might bring a smile. If you want to read about it and see photos, here’s a link to an Audubon article: www.audubon.org/news/seat…

All my very best,

Mark

What a strange and wonderful story. It feels like a modern fable, a small piece of magic in the everyday world. It reminds me of a quote I found years ago in a magic book from the 1970s, attributed to a Dr. Jurvis, whose identity is another mystery to me:

" . . . a harmless mystery, left unexplained, will add to the very meaning of life itself."

Perhaps the “why” of the crows' gifts is less important than the fact that they happened at all.

How to Talk About Your Business, So People Care

You’re talking about your business, and you’re seeing people’s eyes glaze over. You’re listing features, you’re explaining solutions, and nobody cares. Here’s the fix.

To make people care about your business, you first have to show them why you care. To connect with them you have to give them something real.

The Proud Moments Hack

Forget your elevator pitch for a second. Think about the work you do. What are three moments that genuinely made you proud? Not just hitting a sales target. I mean the real stuff:

-

That time your team pulled off a miracle.

-

When you truly helped a customer and saw the impact.

-

The big, ugly problem you helped solve.

These moments are where the magic is. They aren’t just bullet points on a resume; they’re the stories that show who you are and what you’re about. When you talk about them, you’re not a faceless company anymore. You’re a person with a purpose.

Your story is just as important as your product. People want to know who you are, how you got here, and what drives you. The more they get you, the more they’ll care.

Stop Pitching, Start Connecting

What I’m talking about here isn’t about bragging. It’s about being real. When you share a story that means something to you, you create a connection. You’re not just trying to sell something; you’re inviting them into your world.

Your proud moments are your most powerful tool. Use them in your pitches. In interviews. In your marketing. In every conversation.

So, the next time you talk about your business, drop the script. Start with a story that made you proud. Give them a reason to give a damn.

How to Create Ideas and Insights You Can't Find on the Internet or in AI

A note from the author, Mark Levy: I wrote this guide (I believe) in about 2010. In the age of AI, I find its method for generating original ideas more critical than ever. Here it is, lightly edited for today.

This list-making guide is a method for mining your own mind for experiences and insights that exist only there. These are the unique stories, forgotten connections, and nascent hypotheses that have not yet found their way into the world. Because they don’t exist on the internet, they cannot be found or replicated by generative AI.

This is why a manual, systematic ideation technique remains not just relevant, but essential for any thought leader. It is a process for unearthing the very raw material that will differentiate your work. What follows is the original guide. It’s a timeless method for looking at a topic from so many different angles that it becomes foreign to you, forcing you to see it anew and generate foundational ideas.

The Original Text: List-Making As a Tool of Thought Leadership

As a thought leader, you’re hired for your ideas. In a sense, your ideas are your inventory. They’re your currency. Bluntly stated: Your ideas equal money.

The right ideas form the basis of your consulting engagements, media appearances, books, articles, posts, and speeches. Your ideas get you noticed in the marketplace, help you command enviable fees, and enable you to do good work on projects of significance.

When your career is predicated on ideas, however, a complication arises: You cannot endlessly promote the same ideas. One reason is that, as the world changes, the effectiveness of your ideas can erode. A second reason is that the marketplace habituates to your ideas. Prospects think they know what you’re going to suggest, so they turn to other people who tout mystery strategies holding greater promise.

As a thought leader, it’s important that you refine or even restock your ideas periodically, so your brand stays distinct, you stay sought-after, and your business practice stays lucrative.

How, though, do you create standout ideas and intellectual property to add to your business? The ideation technique I’ve used with clients is one you’ve likely used all your life: list-making.

A list constructively narrows your focus. It’s a lens that forces you to ignore most of the world, so you can examine and make decisions about an isolated sliver. A list also coaxes unarticulated and half-remembered information from your brain, so you can better see, understand, and act upon the information.

As useful as list-making has been as a gathering-and-prioritizing device, its worth is amplified when you use it as a tool to produce insights and ideas.

List-Making for Ideation in a Nutshell

Next time you need new ideas, first consider your topic by making a list. Don’t make just one lone random list, though. No single list could give you a suitable view.

You want to look at your topic in a way that’s broad and, in a sense, disorienting. You want your topic to seem foreign to you, so as you study it, surprises, insights, and novel ideas emerge without much effort.

Instead of one list, create five-to-fifteen lists – each with its own focus. These lists would have names like, “What facts come to mind about the topic?,” “What stories come to mind about the topic?,” and “In what ways can I reframe the topic?”

Spread the lists out on a table, look from list to list and item to item, and ask yourself questions, like “What’s obvious here?” and “What’s surprising?”

Human beings are meaning-making machines. In a matter of moments, you’ll find yourself making unexpected connections and seeing unpredicted patterns. New meaning will appear to you, because of the curious vantage point afforded by the lists. You can then turn your latest ideas into “thought chunks,” which you can expand into products and services that support your thought leadership.

That was the nutshell version. Here is the same technique told in detail:

List-Making for Ideation in Detail

Step #1: Brainstorm a Master List

When you need fresh ideas on a topic, start by making an initial list. What type? A list of lists. You’re going to brainstorm the title of every list you could possibly make about your topic. Let’s call the paper you record these titles on your master list.

Some of the titles on your master list might sound generic, like you could use them to study virtually any topic:

- What do I know about (this topic)?

- What don’t I know about it?

- What are all the pieces I could divide it into?

- How can I reframe it?

- What are my assumptions about it?

- What are some facts?

- What stories about it come to mind?

- What images?

- What metaphors and analogies?

- What successes have I had in my work on it?

- What mistakes have I made?

- What excites me about it?

- What scares me?

- Who are the experts on this topic?

Other titles on your master list will be topic-dependent. For instance, if your topic is organizational culture change, some of the titles you could put on your master list include:

- How would an organization know if its culture is changing?

- Why do some culture changes succeed?

- What must an organization give up to change its culture?

- How do you measure the value of a culture change?

- What organizations have I worked with that have had a great culture?

In making your master list, don’t over-think it. Take a few minutes and jot down as many titles as you can, as fast as you can. When you’ve listed thirty titles or so, stop.

Step #2: Explore Your Topic Through Multiple Lists

Look over your master list, and pick a handful of lists you’d like to write. Maybe five, ten, or fifteen different ones. How do you know which titles to select? If an entry feels boring or unnecessary, pass it by. If an entry seems valuable, even if it’s for reasons you can’t explain, choose it. Your gut has its reasons.

Write the title of each chosen list at the top of its own page, and fill in those lists. You can fill in each list one at a time, or you can haphazardly jump back and forth among lists, jotting down items as they occur to you.

Step #3: Make Meaning From Your Fresh Vantage Point

Once you’ve finished filling in the lists, spread them on a table, shuffle them around, and look from list to list and item to item. Ask yourself questions about what you see. Questions like:

- What’s obvious?

- What haven’t I noticed before?

- What’s right? What’s wrong? What’s missing?

- What’s surprising?

- What’s useful?

- What patterns do I see?

- What’s this all adding up to?

By giving your lists time, attention, and curiosity, you’ll see your topic from a perspective that’s wide and uncommon. It’ll be like the first time you saw your hometown from the air. You’ll make fresh meaning from what you’re observing. You’ll notice connections between lists, spot associations among items, discover patterns, build hypotheses, recall stories, and formulate ideas.

While studying your lists, write down your thoughts on a pad as they hit you. Don’t limit yourself to notions elegant or weighty. Get everything down.

Step #4: Build an Inventory of New Thoughts

To finish your list-making ideation session, you need to convert your fragmentary notes into what I call, thought chunks. Doing so will give you a better handle on the ideas, and will help you store them for later use.

What is a thought chunk? It’s a piece of prose containing a complete thought. That prose piece may be a sentence or two or three long. It may even stretch into a couple of pages. Its length isn’t critical. What is important is this: If you read one of your thought chunks – even ten years from now – you’d understand what it meant instantly.

A chunk, then, is a time capsule you create for the future you.

For example, I was once working on ideas for elevator speeches. I scribbled the note “Talking about a movie.” Later, I expanded this into a full thought chunk:

“When looking for distinctions that would fit an elevator speech, most people freeze up. They think finding distinctions is a special skill. It’s not. Finding distinctions is no harder than talking about a movie. If a friend asked about a movie you’d recently seen, you wouldn’t hesitate until you found the perfect thing to say. Instead, you’d instinctively head for something distinctive: ‘It’s about a robot that travels back in time to protect its inventor,’ or ‘It’s the new Daniel Day-Lewis film.’ Finding engaging business facts to talk about in your business elevator speech is no different. It comes naturally if you let it.”

I’ve now captured that idea as a standalone thought chunk. Its meaning is clear and will remain so. I could use the idea now, or a decade from now. It’ll always be at the ready.

Finish your ideation session by converting all your ideas into chunks to store on your computer. You’re building an inventory of fresh ideas, observations, and stories.

Additional Notes from the Original

- Time: A quick session can be done in under an hour. A deeper dive might take three hours, perhaps broken up over several days.

- Revisit: Come back to your lists days or weeks later. Your fresh eyes will see a dozen connections that eluded you the first time.

- Group Work: This process can be adapted for group brainstorming. The group jointly follows the list-making process to solve one member’s problem.

- Organization: Once I’ve written up a thought chunk, I drop it into a separate document on my computer which holds similarly-themed chunks (e.g., “Positioning,” “Sales,” “Writing Technique”). This is far more effective than having ideas scattered across your hard drive. By saving and organizing chunks as you go, you’re tending your lawn regularly so it’s always thick and green.

Modernizing the Method: Tips for Today

The core of this technique is timeless, but the tools we use can make it even more powerful.

Use AI as a Brainstorming Partner. Stuck on your master list? Ask an AI assistant: “I’m trying to generate new ideas about [your topic]. What are 20 different lists I could make to explore this topic from unusual angles?” Use its suggestions as a starting point.

Create a Digital “Thought Chunk” Database. Instead of Word documents, use modern tools like Notion, Obsidian, or Roam Research. These allow you to tag, link, and instantly search your entire inventory of ideas. A simple tag like #thoughtchunk can make them all instantly accessible.

Use Voice-to-Text. Ideas often come at inconvenient times. Use a voice memo app on your phone to capture fleeting thoughts and raw ideas for your lists. You can transcribe them later, ensuring nothing gets lost.

Apply it to Social Media. This technique is perfect for generating a month’s worth of content. The items on your lists can become individual tweets. The connections between items can become LinkedIn posts. A fully developed thought chunk can become a thread or a short article.

Let AI Be Your Editor. Once you have a raw, powerful thought chunk born from your own experience, you can use AI to help refine it. Ask it to “clean up this prose,” “suggest three different headlines for this idea,” or “expand this into a short blog post, keeping the core message intact.”

Getting Started Today

Ready to try? Here’s a simplified guide.

First, Pick a Topic. Choose a subject you want to explore or a problem you need to solve.

Next, Brainstorm Your Master List. Spend 10 minutes writing down the titles of every possible list you could make about your topic. Don’t judge, just write.

Then, Choose and Create. Pick the 5-10 most interesting list titles and spend 20-30 minutes filling them out. Jump between them as ideas strike.

After that, Connect and Capture. Spread your lists out (digitally or physically). Look for patterns, surprises, and connections. Ask, “What’s the interesting thing here?” and write down your emerging ideas.

Finally, Create Your Thought Chunks. Take your best 3-5 ideas and write each one out as a complete “thought chunk.” Give it a clear title and save it in your new idea inventory.

In a world of content abundance, the new thought leadership is not about creating more content, but about creating different content. It’s about depth, originality, and a unique point of view. This method is a reliable engine for producing exactly that.